See yourself in the star mirrors of Machu Picchu

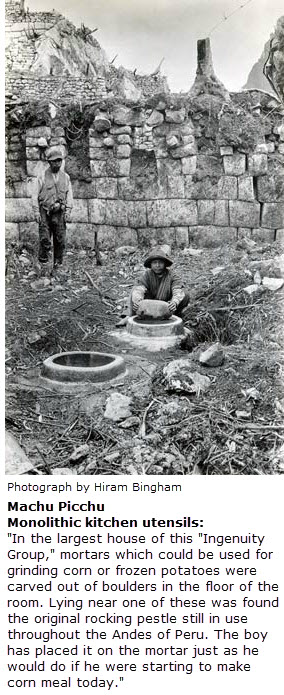

When Hiram Bingham embarked on his second, more thorough, expedition to Machu Picchu in 1912, he came upon two large bowl-shaped objects hewn into a solid granite floor.

He was sure he had stumbled into the Inca’s kitchen.

Bingham even asked one of his Indian workers to pose with a large stone “pestle” laying nearby to demonstrate his conclusion.

For decades, that interpretation held sway.

But somewhere halfway between Bingham’s death in 1956 and the centennial celebration of his “scientific discovery” of the Inca Citadel, researchers started to dispute that interpretation, as they did many of his theories.

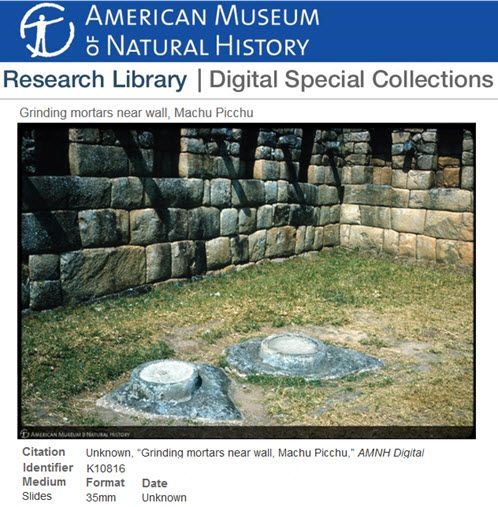

For one thing, “the depressions are far wider than historical or current Andean mortar-stones would suggest,” noted Hugh Thomson, author of terrific, must-read books, like Cochineal Red and The White Rock: An Exploration of the Inca Heartland.

In the 1970s, from the burgeoning field of archaeoastronomy another interpretation began to form, and took hold.

If you filled the impression with water, they were transformed into reflecting pools — unmoving mirrors — that Inca astronomer priests could have used to track the movement of the constellations and planets.

They might have used the reflection to safely watch the passage of the sun across the zenith.

Today it is generally accepted that Machu Picchu was the hub of a vast complex of astronomical observatories. The Inca cosmovision was integrally connected to dates in the agricultural calendar.

In a way, there was a connection to food.

In a very tangible sense, marking the rising sun on the June solstice and the heliacal rising of the Pleiades constellation was what to Inca did to feed a vast and expanding empire.

If you like this post, please remember to share on Facebook, Twitter or Google+

Peru Scrabble® Tour & Tournament Oct. 4 – 12, 2013

Peru Scrabble® Tour & Tournament Oct. 4 – 12, 2013  Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival  The Unforgettable Statue of Jesus Christ in Cusco

The Unforgettable Statue of Jesus Christ in Cusco  El Paraiso: The boom and bust of Peru’s cultural patrimony

El Paraiso: The boom and bust of Peru’s cultural patrimony  What happens during the Inti Raymi ceremony?

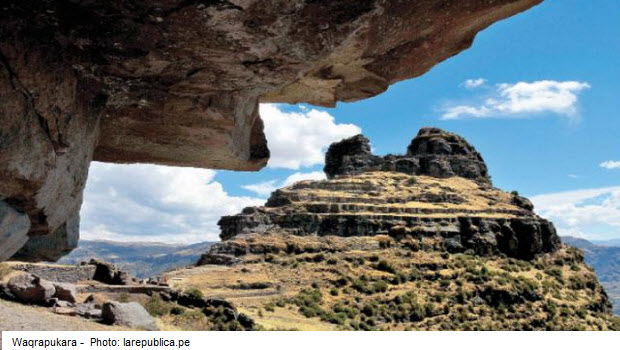

What happens during the Inti Raymi ceremony?  Treasure of Waqrapukara – a lesser known Inca sanctuary

Treasure of Waqrapukara – a lesser known Inca sanctuary  Peru president takes his helicopter for a spin around Machu Picchu

Peru president takes his helicopter for a spin around Machu Picchu  Machu Picchu visitor entry in two shifts set to begin this month

Machu Picchu visitor entry in two shifts set to begin this month