Disputed landladies of Machu Picchu seek humongous back rent

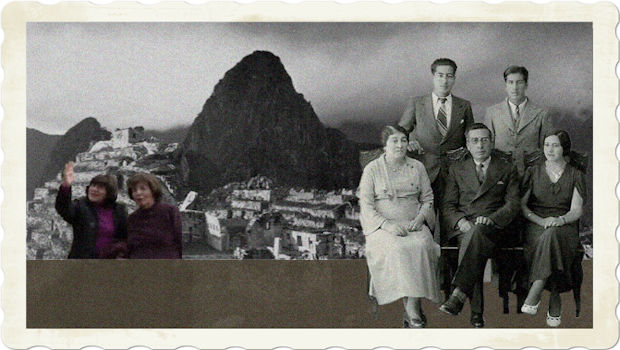

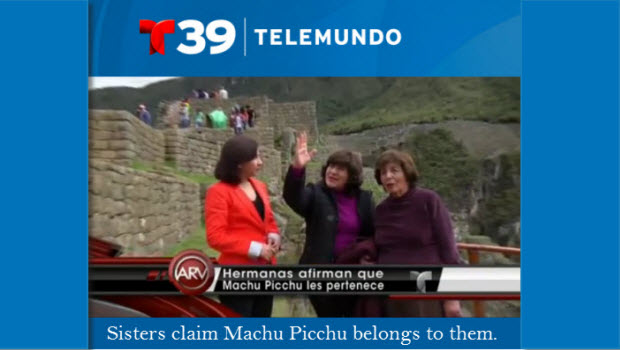

The sisters, in their late 50s, perhaps early 60s, stand in line to enter Machu Picchu. Once inside the ruins, they make their emotionally charged claim that they’re the rightful owners of the iconic Inca citadel.

“It’s incredible that, being descendants of the sole owner of Machu Picchu, we have to pay to enter our property,” Roxana Abrill declared. “Oh, all the memories, from the time we first came here as little girls with my mother, with my father, when the paths weren’t so packed with tourists.”

“I feel nostalgic, many memories,” her sister, Gloria Abrill, said wistfully, her voice cracking. Asked why she was crying, she replied: “What was ours isn’t ours anymore.”

That was the news story that ran in November 2013 on a Spanish-

Their seemingly preposterous claim isn’t as unhinged as you might think.

It’s actually gotten prominent mention over the years in the New York Times, the Telegraph and NPR.

But the Abrill family’s story was first covered in 2006 by journalist Sergio Vilela for the magazine Etiqueta Negra, and later translated into English for the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Vilela then got together with Texas State University historian José Carlos de la Puente and spent the next four years expanding the article into the 2011 book El Útlimo Secreto de Machu Picchu: Quién es dueño de la ciudadela de los Incas. (It’s a book that really should be translated into English.)

Roxana Abrill, a trained historian and museum curator, has spearheaded the high-profile legal battle to be compensated for her family’s loss of Machu Picchu. She wants Peru to pay her family 100 million dollars, plus a cut of future tourism profits.

El Útlimo Secreto de Machu Picchu offers her family’s version of the Peruvian government’s alleged misappropriation of their property. Framed in a fluid and engaging human interest narrative, the book cites voluminous documents and family correspondence.

Abrill’s great grandfather, Mariano Ignacio Ferro, owned the 22,000-hectare hacienda, of which Machu Picchu was a part, in 1911, when Yale professor Hiram Bingham arrived to “discover” the lost ruins.

“Machu Picchu never was lost,” Roxana Abrill protests. Her great grandfather’s employees lived at the site when Bingham was escorted there by a local child.

And Bingham himself acknowledged Ferro’s assistance. It was on Ferro’s orders that some 40 laborers from the estate helped Bingham clear the ruins between 1912 and 1915.

As Machu Picchu transformed into a Mecca for foreign archaeologists, Ferro in 1921 turned over management of the hacienda to his daughter Tomasa and her husband, Emilio Abrill — Roxana’s grandparents.

Emilio Abrill, who had served as mayor of Cusco and later as a senator, was the one who approached the Peruvian government in 1928 to suggest the state expropriate Machu Picchu and the surrounding ruins. A year later, Peru implemented its cultural patrimony law, designating archaeological sites and historical monuments property of the state, while recognizing the need to compensate and indemnify affected property owners.

In 1933, Abrill formally requested that the state expropriate his land and manage the archaeological ruins. He waited for a year and a half before he received a reply.

“Supreme Resolution Nº 2511: By agreement of the Council of Ministers, the solicitude for expropriation has been accepted.”

The letter signaled the government’s explicit acknowledgement that since Machu Picchu was within a private hacienda, the state should pay him a fair market price for it.

But what should the compensation be for what was then an amazing, but still virtually inaccessible Inca citadel, perched on the saddle of a mountain between two craggy peaks?

In a prophetic letter to his attorney in 1935, Emilio Abrill pondered the question:

“We are talking about wonderful ruins of incalculable value,” he wrote. “By the same token, they attract the admiration of scholars from around the world. They could provide to the owner a great fountain of resources, such as an ‘Archaeological Museum’ — benefits that the state must perceive if it is to systematize, enhance and intelligently market (the ruins) for tourism.”

The government dispatched an engineer, Carlos Ugarte, to assess the value of the overall estate. But that didn’t work out too well.

“The undersigned considers himself unable to proceed with the ordered valuation,” Ugarte concluded. “How much are these forests worth that contain millions of square feet of wood, with a railroad line at its feet?”

In other words, the government’s assessor had thrown his hands up and deemed the property… priceless.

“When he received the assessment, Senator Abrill himself proposed a form of payment, which today seems absurd for both its strangeness and its generous enthusiasm,” Sergio Vilela, the journalist who first broke this story, wrote.

In exchange of his family estate, Abrill offered to accept a comparably sized area of land along the Pacific coast. He also proposed, as an alternative, that “the state buy wood from his forest land to manufacture the seats of trains that would eventually run through the area,” Vilela wrote. “Not a bad idea, but it still amounts to trading a gram of gold for a gram of sand.”

For years, the government failed to respond.

Tired of waiting, Emilio Abrill in 1944 sold most the estate to a local farmer and business associate, Julio Carlos Zavaleta, making him owner of “an area full of Inca trails, agricultural terraces and aqueducts.”

But Abrill still believed the government would eventually make good on its obligation, so he didn’t shirk his end of the bargain. The property sale record stated clearly: “Not included in this sale is the payment of compensation pending before the government for the expropriation of the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu, Huayna Picchu, Wiñayhayna, Sayacmarca and Phuyupatamarca, currently held by the state.”

Senator Abrill died believing that although he and his wife had not been compensated for Machu Picchu, his children would be. But neither they, nor their children, ever received a cent.

The Abrill family filed suit against the Peruvian government in 2004, and were joined in the legal action by the Zavaleta family.

Machu Picchu was only officially registered as property of the state in 1995. The lawyer for the Abrill and Zavaleta families argues that the filing was badly botched and that the state’s property registry is invalid.

Peruvian government lawyer Elias Carreño is quoted in Vilela’s book saying that Machu Picchu “belongs to all Peruvians.”

The descendants of Emilio Abrill and Julio Carlos Zavaleta lost any claim to Machu Picchu, he said, when it was declared a Peruvian Historical Sanctuary in 1981. UNESCO declared the entire zone a World Heritage site in 1983.

In June 2011, Roxana Abrill and Julio Zavaleta wrote a letter to UNESCO, hoping the UN heritage body would intervene on their behalf.

No luck so far.

You Might Also Like: Machu Picchu Guide

Airlines to Peru and the runways of aviation history: Peruvian airport names

Airlines to Peru and the runways of aviation history: Peruvian airport names  Andean conceptions of the afterlife

Andean conceptions of the afterlife  Visit Sacsayhuaman to ponder an awesome megalithic mystery

Visit Sacsayhuaman to ponder an awesome megalithic mystery  Matthew Parris sings the praises of a night aboard the Yavarí on Lake Titicaca

Matthew Parris sings the praises of a night aboard the Yavarí on Lake Titicaca  Lima’s legendary leaping monk saves drowning man

Lima’s legendary leaping monk saves drowning man  Casta paintings: Historical testament of the African diaspora in Peru

Casta paintings: Historical testament of the African diaspora in Peru  The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter

The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter  The Inca Sun of Suns Could be Returned to Cusco – by Donald Trump?

The Inca Sun of Suns Could be Returned to Cusco – by Donald Trump?