The story of the bewitching Perricholi

In a verdant valley outside the provincial capital city of Huanuco lies the “village of bewitchment” Tomayquichua, the legendary birth place of one of Peru’s most famous Colonial-era women, Micaela Villegas, the “Perricholi.”

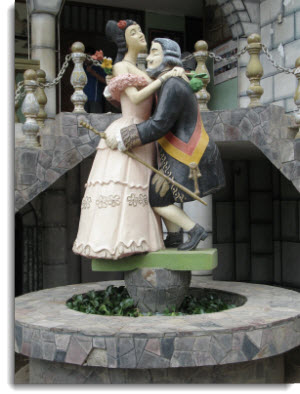

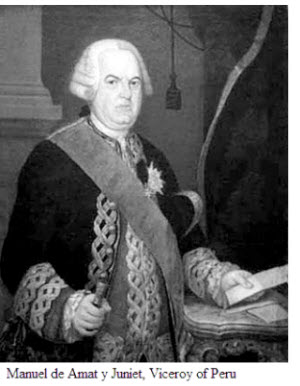

This young stage actress’ most famous role was as the seductress of the Spanish Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Junient, an aging bachelor and military officer more than three times her age. Their stormy, scandalous affair has served for centuries as an inspiration for operas, plays and novels.

Mérimée’s Carrosse du Saint Sacrément, Offenbach’s opera La Perricholi, and Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey are just a few of the more notable examples.

The name La Perricholi, is believed to be derived from the Catalan pretichol, or “pretty little thing.” Legend and historical record clash as to whether it was Amat, himself, who corrupted the endearing term into perra chola — or “half breed bitch” — during a heated lovers quarrel, or Peruvian aristocrats, hostile to Amat’s colonial administration and his torrid relationship with a lower-class mestiza woman.

Instead of shrinking from the derogatory slur, Micaela embraced the name, and went on to wage a magnificent professional comeback, dominating Peruvian theater under the stage name “La Perricholi.” She enjoyed a long, fruitful career that lasted long after Amat was recalled back to Spain in 1776 and well into the 19th century.

According to historical records, she died in 1819 at the age of 71.

Below is one version of La Perricholi’s life, as retold by American novelist and travel writer Blair Niles in her 1936 book A journey in Time – Peruvian Pageant.

Enjoy!

If you like this post, please remember to share on Facebook, Twitter or Google+

~ The Viceroy’s Mistress ~

Once upon a time then, there was a little girl named Micaela Villegas. She was a chola child which means that both Spanish and Indian blood went to her making; she was born in the Sierra at a place called Huanuco. But when she was five years old, in the year before the “Great Earthquake,” her mother brought her down to live in the capital city of Lima, not far from the sea, where you are never too warm and never too cold, a place gentle and balmy, where the act of living is pleasantly easy. And this was in the city’s proud days, when its streets were full of gilded carriages, paneled in florid design and lined with brocade in brilliant colors, while for the nobility there were magnificent coaches drawn by four mules.

People used to speak of Lima as a city of more than four thousand carriages. There were cavaliers, too, in graceful capes which swung with the motion of their horses.

Pleasure was the business of life, and there were so many slaves that no one of them was overburdened.

But to support the luxury of Lima, on the haciendas of cotton and sugar cane slaves were slaves, and in the mines of the Sierra, Indians toiled that Lima might live in this picturesque pomp, where only those predisposed to sainthood ever thought of saying “no” to the flesh.

This was Lima in the voluptuous eighteenth century, the century of Madame du Barry and La Pompadour, of Versailles, of Marie Antoinette and the Petit Trianon. Great caravans of mules brought into Lima what the city required from the haciendas, and from the port of Callao the fine merchandise arrived by sailing ships from Europe and the Orient. So many caravans of mules that the streets were full of their dung, which in the dry season disintegrated into a dust which drifted like smoke, with the passing of carriages and coaches and mounted gentlemen.

To a little girl from the Sierra the fine ladies of Lima were astonishing in silks and velvets which opened in front to show petticoats flounced in the best laces of Europe, lace bodices low over their bosoms, and jewels sparkling in their ears, in their necklaces and their bracelets; even in their girdles and in the buckles which adorned their tiny shoes. Equally fascinating these ladies were, too, when they shrouded themselves in black mantes and went about the city showing just one great dark eye, so that you did not know who they were, and were kept guessing.

Travelers of long ago have described this Lima to which little Micaela had come down from the Sierra. And invariably they were impressed with the Moorish quality of the city. The domes of its churches reminded them of Mohammedan mosques, while the patios, the flowers, the trickle of fountains, the flat roofs, the horseshoe arches, the stretches of blind, mysterious walls, the gratings, even the veiling of women when they walked in the streets, these were all Moorish legacies transplanted from Spain to Lima, far away in the New World.

A child never tires of the life in the streets and to one like Micaela, with a genius for mimicry, the street cries of Lima would have provided never-ending diversions.

There was the milk-seller calling in the very early morning. At that hour, too, there was the woman selling herb teas; mate from Paraguay, manzanilla, native to Peru, and baldo which comes from Chile; each tea claiming to regulate human ills and to prolong life.

La lechera! La tisaneral Calling up and down the streets.

You could tell the time by these street cries. The tea-woman and the milk-woman-that meant six o’clock.

And it would be eight o’clock when you heard the man calling buns-for-sale. At ten, there was the tamale woman; at eleven, the melon-woman sang; at twelve, the man with fruit, oranges and figs, alligator pears, the fruit of the passion-flower, chirimoyas and grapes. And at the same hour a man who sold peppery little mincemeat tarts. At one, men with alfalfa to feed Lima’s mules and horses, little donkeys so loaded with alfalfa that they seemed like moving stacks of grass, to each of which had been attached a donkey’s head and tail. At two o’clock there were maize-cakes, at three the taffy-man, at four the pepper-woman and at five a man who sang of the flowers he carried:

“Here is a garden! A garden! Lassie, don’t you smell it?” And when his cry had died from the street there came at six o’clock the poultry-man, at seven the caramel-man, at eight a man who sold ice-creams and another with wafers rolled very thin.

Then at nine, at the bell to cover up the fires, there came, each in a red cape and each with a lantern in his hand, those who begged alms for the souls in Purgatory.

Then it was time for Micaela to go to bed; to sleep until the milk-woman and the tea-woman came to wake the world. And if a little girl was born an actress she could reproduce these cries of the hours.

It was a period when women got on with small education; elementary religious instruction and some training in music was thought sufficient. But Micaela’s talent was an impetus to go further. She learned to play with skill on both the harp and the guitar. She had a voice so full of harmony that inevitably she sang to their accompaniment. And her memory was so quick that while she was still a child people were delighted with her recitations. Even as a little girl she could give scenes from the gallant capa y espada dramas, and from the comedies of Lope de Vega, Calderon de la Barca, and Juan de Alarcon.

Naturally the lines which she so early memorized from these authors had a part in the fashioning of her mind and her spirit.

Lope de Vega stimulated her own wit, and taught her to live in the world of the imagination. He appealed to her natural gaiety, and introduced her to the history and legends of Spain.

The Corpus Christi plays of Calderon de la Barca were full of a mysticism which could not fail to appeal to the Indian in Micaela, to the capacity for profound worship so strong in the race.

While Alarcon, the hunchbacked, red-bearded genius of Mexico, spoke to her in the spirit of her native America as well as of Spain. That exotic quality in his work which his fellow writers in Madrid had found so disturbing, so irritating, because unfamiliar, would not have been strange to Micaela with her fusion of the two bloods.

As she grew older she must have felt it a bitter thing that he had been so cruelly attacked by the Spanish writers, that in their dislike they should have ridiculed even his physical deformity; and that it should have been left to the great Frenchman, Corneille, so to value his work that he said he would have given his own two best dramas to have been the author of Alarcon’s La Verdad Sospechosa. Alarcon had been dead a hundred years when Micaela was born, but all that he had suffered seemed still to endure in the lines he had written:

“Próvia naturaleza,

Nubes congela en el viento,

Y repartiendo sus lluvias,

Riega el arbol mas pequeña.”Thus Alarcón would have taught Micaela compassion for the unfortunate. While the artistry of the lines which he so carefully composed and polished, with such regard for restraint and for style, must have influenced her great respect for her art, which is a thing remote from any vanity of the ego.

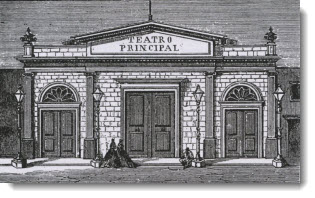

When Micaela was twenty the thing happened for which she had been created. She got her chance to appear on the stage, and immediately she was the sensation, the darling of Lima’s one playhouse: in return she gave to the theater a love of her art which never knew any rival.

And of course her mother, and the brother Felix who all his life adored her, exulted in her instant success. Their Miquita – in the pretty diminutive of intimacy – their Miquita was all at once become the first actress in Lima, to them the first actress in the world. If proof were needed, there was the contract with Maza, impresario of the theater…

Imagine Miquita with a contract and a salary of a hundred and fifty dollars a month! So glittering a thing is success, a sun in whose warmth those who love you, who have believed in you, may bask content, justified.

Now when Lima was not talking of “La Villegas,” as they called Micaela, they were speculating upon what sort of man would be the new Viceroy, expected soon to arrive. The beauty of La Villegas, her latest role, her newest song, alternated with exchange of information about the Viceroy, Don Manuel Amat, who was on his way from Chile.

Everyone wanted to know if he was married. And when it was learned that though he was past sixty he was still a bachelor the news sped through Lima.

“Though what good it does you all, I can’t see,” said a shrewd old marquise, “since you know perfectly well a viceroy is forbidden to marry within his jurisdiction. And a good rule too, or the mothers with daughters in the market would claw each other’s eyes out.”

It was in the lovely month of December that the new Viceroy arrived at the beginning of Lima’s summer, when the crepe myrtles are blooming like rosy clouds drifting through green foliage, and the jacandra trees border the avenues with bouquets of lavender, and in the roadside willows, Bocks of small birds twitter and sing all day, and the air is clear, with no more mist to veil the city until May shall come again.

To welcome this new Viceroy, the balconies were hung with banners and tapestries and triumphal arches had been set up along the way by which he was to pass. The cavalry led the procession, followed by the artillery, the city militia and the troops of the line, the university professors in their robes, the members of the audience on horses covered with trappings of black embroidered velvet, the magistrates on foot in scarlet velvet robes, and then the Viceroy. What would he be like, this Don Manuel Amat, who was come to rule Lima?

Micaela looked at him certainly with the eyes of a woman used to appraising men.

The Viceroy came on horseback with two of the city aldermen in their official robes, on foot, leading his horse, while eight members of the Corporation, also on foot, supported a crimson and gold canopy over his viceregal head.

They had said that he was past sixty but his face seemed younger than that. It was a round plump face, smooth shaven beneath grey hair worn long enough to be curled up over each ear in a soft roll.

The outgoing Viceroy’s hair was longer and curled under.

Arnar’s shorter, upturned cut raised the lines of his face and at the same time lifted the years, directing attention to his dark widespaced eyes under their well-marked brows. His figure, too, had a young upstanding air. After all, he had been an army man from the beginning.

As for his dress, even the King could not have been more impressive than this Viceroy riding with royal pomp under a canopy of gold and crimson, while in the plaza, the Archbishop waited to receive him with all the honors of the Church.

And when the days of celebration were over, and there had come at last an end of speech-making and feasting and bull-fights, it appeared that the new Viceroy’s favorite diversion was the theater.

And upon sight he loved Micaela Villegas to madness. Was she so beautiful?

Not, Ricardo Palma says, if by beauty you mean an orthodox regularity of features, but if you find beauty in supreme grace, then Micaela was irresistible.

She is described by one who knew her as being very small, with a rounded figure and the tiny hands and feet so characteristic of the Peruvian Indian. Her bosom was full, “turgente” as her contemporary puts it, and such a bosom was the fashion of her day. She had exciting shoulders and a beautifully turned neck. Her face was a delicate oval of pale olive, lit by bright black eyes and tiny brilliant teeth. Her lips were full, like her bosom, and on the upper lip was a provocative little mole. For her nose, he does not say much, and he adds that, here and there, her skin showed the marks of smallpox which she managed skillfully to conceal with the aid of cosmetics.

She understood how to dress with a taste extremely restrained in spite of the flamboyant tendency of the time.

This Micaela Villegas possessed evidently the magic of creating that illusion of beauty which is a thing, after all, more potent than mere beauty itself.

Without having been born in Lima she had succeeded in making her own all the seductive charm of the Limeñan which through the centuries has led men to devote pages of serious Memoirs and Histories to the fascinations of the women of Lima.

And Micaela had them all, the tang of a salt-and-pepper wit, the lively fancy, the vivacity, the coquetry, the tenderness, and the gift of making people happy, making them pleased with themselves. To these qualities she added a great love of the beautiful and the noble, and a spirit deeply religious. The combined traits were essentially Spanish, while the necessity to worship was profound in her Indian blood.

For Micaela was a chola of the Sierra as well as a seductive Limeñan.

To the Viceroy, Don Manuel Amat, in his box at the theater, she was more even than all this: to the dying fires of his age she was tremendously alive. His experience showed him at once how vivid an intelligence and eager an imagination she brought to the roles she played. And he loved her with the extravagant folly of maturity.

His infatuation could not have been concealed, and he made no effort to hide it. All Lima knew that the Viceroy had fallen in love with La Villegas.

His very titles made the mind dizzy:

His Excellency, Viceroy and Captain General of Peru, President of the Royal Audience, Superintendent of the Royal Finances, Director General of Mines, Knight of the Order of San Juan — It was quite impossible to remember them all. But in a word he was representative of the King himself and responsible only to him. And he loved her Miquita to madness. The whole of Lima knew it.

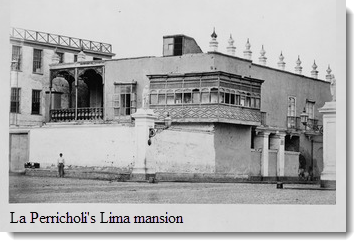

The aristocracy, not then sufficiently intelligent to pride themselves upon any save royal Indian blood, raged that their Viceroy should be the slave to a chola actress, a half-breed girl from the Sierra, but their raging did them no good. Actually the Viceroy was building a palace for Micaela, and it was not long before she was riding in his retinue when he drove out in the viceregal coach.

God be thanked, they said, that a Viceroy was prohibited from marriage within his jurisdiction.

Nevertheless Micaela gave Amat a son and had the effrontery to name him Manuel Amat.

The hope that he would tire of the girl passed with the years. Micaela went on acting and the Viceroy went on adoring her. As for the grandmother of the little Manuel, her airs were infuriating to the haughty grandees. She had a habit of calling from the balcony:

“Keep out of the sun, child. Remember that you are not a nobody…”

“Quitate del sol, niño, que no eres cualqulera, sino hijo de cabeza grande.”

And this arrogant presumption which so exasperated Lima was handed down through the years until Ricardo Palma perpetuated it in print.

Meanwhile the Viceroy was growing a crop of enemies. For, as though his imbecility in the matter of Micaela were not enough, he made himself further detested by his strict carrying out of the King’s every edict, being especially offensive in scrupulously collecting the King’s revenues.

But nobody could say that Amat did not work hard for the good of Lima. He had reorganized the army. He had under construction a new bullring and a cockpit. He was himself personally directing the building of the Church of the Nazarenes and restoring the tower of Santo Domingo so greatly damaged by a great earthquake, and he was planning new avenues and plazas. He saw Lima as the Versailles of the New World.

But he continued to love Micaela, and that was not forgiven him.

Meanwhile Micaela laughed and sang and delighted her Viceroy. She might so easily have given herself up to luxury and pleasure, and to lolling on the low, cushioned dais – another of the Moorish legacies transplanted to Lima. For her diversion she would have had her guitar and her harp, and there were the parties at the palace where she met the most distinguished men of Lima.

But none of these compensated for the theater. First and last Micaela was an actress. The Viceroy’s adulation never touched that. It was perhaps this fact that she might never be wholly possessed that held Amat.

And in her devotion to her own profession of course she understood his ambition to excel as a viceroy.

Through all that troubled time of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Peru, Micaela’s companionship must have been his comfort. The banishment of the Jesuits was a business of immense difficulty, and Amat knew well enough that it would increase the already disturbing number of his enemies. But the command had come in the hand of the King himself, sent out from Spain by a special messenger, and it was Amat’s duty to carry it out in every detail. The Jesuits were powerful, with many relatives and connections. It was necessary to act with complete secrecy, arresting and assembling members of the Order all over the country, at the same time that a ship was made ready to take them out of Peru. It was a difficult, dangerous business, and the Viceroy needed the comfort which was Micaela’s to give. The mere presence of such a woman is like the hypnotic touch of tender stroking fingers driving out care, refreshing the mind, preparing it to resume its burdens.

In all Micaela’s life these must have been the happiest years. Amat was still a fine specimen of a man, with a shapely leg inside his silk stockings, a figure which set off well his embroidered jacket and waistcoat, and under their fine lace ruffles his hands were not yet aged, while his upturned rolls of grey hair crowned the whole man with distinction. True he had lost some teeth, but Micaela’s admiration of achievement could overlook a mere matter of teeth.

Meanwhile the eighteenth century was advancing toward its close. In France the Pompadour had died, the King had replaced her with Madame du Barry, and in the Colony of Virginia, Patrick Henry was beginning to talk about liberty or death, though few yet dreamed of such a thing as freedom for slaves. Still his words, like far off thunder, presaged a storm.

But in Lima it seemed as though life would go on forever as it was, “ancha y lenta” a broad leisurely stream of pleasure, with gallantry the supreme business of existence.

Micaela’s life in those days seemed cloudless. She knew, naturally, that aristocratic Lima detested her, that it would hurt her if it could. But what of it? Even the sneer of “chola” could not touch her. What did the taunt of “half-breed” matter while on the stage she could still fascinate, by her every word, her every movement, by her song and her beauty? After all, in spite of their jealousy of her they, too, were her slaves really.

Surely nothing could ever alter her radiant life. The Viceroy had loved her for eleven years. She was not afraid of losing him, for he had not so much as listened to the cabal against her. And to the prestige of hispatronage, to the glamour of their relationship, there was added the deep satisfying joy of acting.

Then, in a moment, she herself shattered her own paradise, as the great earthquake had suddenly without warning destroyed the Lima she had first known.

As quickly, as unexpectedly as that, her paradise fell into ruin.

It happened at the theater. The play was Calderon de la Barca’s Fuego de Diós en el querer bien! Maza, the impresario, had the role of the gallant. Micaela played the lady role.

For some time past she had suspected that Maza was showing partiality to a new actress, a certain Inesilla. Now, as Micaela was reciting her lines, Maza murmured low in her ear: “More spirit, woman! More spirit!

Inesilla would play it better.”

Micaela then forgot everything; forgot the audience, the Viceroy in his box, everything but the injustice,the insult of Maza’s words. And instantly she raised a whip which she carried in her hand, and struck Maza across the face.

The curtain went down upon a house shouting, “To prison with her! … To prison—”

In his box the Viceroy turned the red of a crab. It was long told in Lima, and recorded by Ricardo Palma, that the Viceroy was as red as a crab when he left the viceregal box.

And with his going the performance for that night was abandoned.

So it was that Micaela Villegas destroyed herself.

She had done what was to the Viceroy an inexcusable thing; she had made a disgraceful scene, and she had been justly hooted by the audience. He, the Viceroy, as her lover, felt that the insult was his as well as hers. He had ignored the enmity brought upon him by his love of her, but, as representative of the King of Spain, he could not condone that outrageous scene. Micaela had put herself in the wrong.

Late in the night, when the Viceroy thought that Lima slept, he went with a lantern, cautiously through the dark streets to Micaela.

“It is all over,” he said. “All that has been between us is over. And you should be grateful that I don’t order you to go tomorrow to the theater on your knees to beg pardon of the public.”

And then he said goodbye: “Goodbye, Perricholi.”

He would have flung at her the scornful taunt, “Perra chola” — “half-breed bitch.” But the words emerged as “Perricholi.” Afterward it was said that in his anger, what with the absence of certain lost teeth, and what with his Catalonian accent, the Perra chola, the insult he would have hurled out of his sore heart, became Perricholi:

“Adiós, Perricholi!”

So Micaela, who had been the petted actress, La Villegas, came to be known as La Perricholi in disgrace with the Viceroy and not permitted to appear on the stage of Lima’s playhouse.

“That’s the end of her,” people said, as the months passed and Micaela went no more to the palace and rode no more in the Viceroy’s retinue. All the best roles were now InesilIa’s. La Villegas was forgotten. La Perricholi was that ignominious thing, a fallen favorite.

Thirteen years the first actress of Lima, eleven years mistress to the Viceroy, she was well accustomed to the enmity of the jealous, but enmity sweetened with envy is a different matter from triumphant contempt.

And because the bitterness of failure lies much in its effect on those most dear to you, Micaela must now have heard with agony her mother’s voice calling from the balcony to the little Manuel: “Quitate del sol, Niño; Remember you are not anobody —”

The familiar words were uttered with a plaintive attempt at their former arrogance.

And Manuel, Micaela was ambitious for him. He was to have been educated, taught Latin even; perhaps one day to be a viceroy like his father.

And always she must suffer the thought that at the: theater Inesilla was playing her roles, singing her songs.

The theater was Micaela’s life and she had lost it.

But for her comfort there: was Felix, the brother who had never failed her…. Surely there must often in those: days have: come to her the lines from the hunchbacked poet who had known how deep scorn cuts into the soul.

“Diós no lo da todo a uno…

Próvida naturaleza

Nubes congela en el viento,

Y repartiendo sus lluvias,

Riega el arbol mas pequeño;”“God does not give all to one…

Beneficent nature

Gathers into winds the clouds,

And dispersing the showers,

Refreshes even the smallest tree.”What folly to have believed that God would give all to one!

Just because for a time all had seemed to be hers. But it was beyond question difficult for one who had been La Villegas to become used to being only La Perricholi.

In her banishment there were inevitably tongues to bring to Micaela news of the Viceroy. The Viceroy, so these gossips said, was much concerned that robbers were grown so bold that nobody dared go out at night without sending ahead several slaves with lanterns. And Amat had set himself to arrest the whole brazen gang.

However sad of heart he might be, a viceroy could go on with his work, but for an actress without a stage, without an audience, there was nothing. The days were long without new roles to learn and rehearse, the nights were intolerably lonely. Perhaps the Viceroy had forgotten.

Lima buzzed with the Viceroy’s prosecution of crime, and then it was known that the criminals had been arrested, proved guilty and sentenced.

In the great square then, the convicted were hanged, and the women who had been accomplices, their heads shaved, were made to walk three times under the gallows, and sent then to the prison to receive each fiftylashes.

The Viceroy was tireless. Now he announced that Lima must be properly lighted, and he made it compulsory that a lantern should burn all night before the door of every private house, and that, at the expense of the shopkeepers, there should be lanterns burning on every street-corner.

Perhaps, Micaela must often have thought, in all this activity he had no time in which to miss her. But it was not easy to forget Micaela. The theater was not the same without her. The palace rooms which she had filled with laughter and with the rustle of taffeta were as rooms whose light had been put out.

Lima itself … of what use to have lanterns burning before every door and at street-corners, when for him, the light of it all was gone?

And then there was Manuel … he would see his little son. Finally thus Amat came to the end of his endurance.

Viceregal indignation, viceregal pride could no more hold out against his longing for Micaela.

And Amat went back to Micaela.

“Keep out of the sun, child,” Manuel’s grandmother called from the balcony; once more the happy number of a Viceroy’s titles, spinning like a merry-go-round in her brain: Gentleman of His Majesty’s Bedchamber, Superintendent of the Royal Finances, Knight of the Order of San Juan, Lieutenant-General of the Royal armies, His Excellency the Viceroy of Peru, representative of the King himself …. And all this had come back to Miquita, her Miquita, just a chola child, born far up in the Sierra.

Was there ever more noble a sight than the Viceroy stepping from the viceregal coach, coming back to Miquita? The very dung that his six mules deposited before the door while they awaited His Excellency was royal dung.

But Micaela was thinking of the theater, which was her life, explaining to Amat that she must return to the stage.

She would make the name “La Perricholi” — that contemptuous gibe which had fastened itself upon her — she would make it as brilliant as ever “La Villegas” had been.

La Villegas — that was the past. La Perricholi should be the shining future.

But for all her high spirit Micaela came trembling upon the stage on the night of her return. Then it was Amat himself who cried encouragement from the viceregal box:

“Courage and sing well!”

And never in Lima had there been anything like the ovation that was La Perricholi’s on that night.

Micaela was intoxicated with the success of the Perricholi. There had always been in Lima an unwritten law that only the nobility of Castile might ride in coaches drawn by as many as four mules; others, no matter what their wealth, must be content with a lesser number.

And there now came to Micaela the idea that she would scandalize this aristocracy by setting up for herself a coach-and-four. The coach should be decorated in gold, with panels elegantly painted. Postilions in a livery trimmed with silver should mount the mules, and there should be lackeys too, also in livery. So would she drive through the streets to the dismay of all who had gloated over her humiliation.

This had been perhaps a fantastic dream, fashioned in an hour of despair. Now, down to the smallest detail, it came true. And Micaela, in silks and laces and jewels almost as costly as the wardrobe of the image of Our Lady of Rosario in the Church of Santo Domingo, set forth in her coach-and-four to ride through the streets of Lima.

But there, in the street of San Lazaro, went the Parish priest on foot, taking to one who lay dying the last Sacrament — the Viaticum. Following the priest was an acolyte with a tinkling bell to announce their coming, so that all might fall to their knees in homage to the passing of the Host.

Micaela then felt her heart break that she should ride in the pomp of four mules, while the body of Christ was carried in humility, and she stopped the coach and ran to the priest begging him to take her place in the carriage.

So, in the end it was the Sacrament that drove in the magnificence of coach-and-four, while Micaela, her triumph washed in tears, followed on foot.

The coach, its mules, its postilions and lackeys in livery, she gave to the Parish, to be used only when the Sacrament was summoned to the dying.

The individual life falls into epochs, much as the life of the world is separated into centuries; both in turn further redivided into smaller units of experience. And now Viceroy Amat was being retired; he would go back to Spain for what of time remained to him on earth.

And Micaela? People wondered about Micaela. Would she go with him? Or why didn’t Amat himself remain? He was old and had been absent many years from Spain.

But the Viceroy sailed away forever and Micaela stayed on, the famous Perricholi of Lima’s theater. Perhaps they both realized that what had been between them had gradually faded out of existence. And it was not in Amat’s nature to live where he must see a successor ruling in his stead, while for Micaela it was too late to risk establishing herself as an actress in a new country. She clung to the city where she had made her place.

It was better so for them both. The fourteen years of their union thus came very quietly to its end. Yet, though it passed from the visible and the actual, it still survives in the ghost-world of Lima.

Change was coming, too, to the aging eighteenth century. As it approached its close it broke into fragments, as though shattered by some missile hurled with deadly aim out of space, destroying much that had long been familiar.

In North America a Revolutionary War had been fought and won by Colonies which then formed themselves into the United States. In Venezuela a child named Simón Bolivar had been born. In France heads were falling under the guillotine. But in Lima, beyond the outgoing of one Viceroy and the incoming of another, the life-stream flowed still wide and slow.

The young Manuel de Amat was having his Latin lessons, Micaela was playing at the theater, and there was a new actor, Don Fermin Vicente de Echarri, who had become her friend. She had entered upon a period devoted to the quiet satisfaction of work.

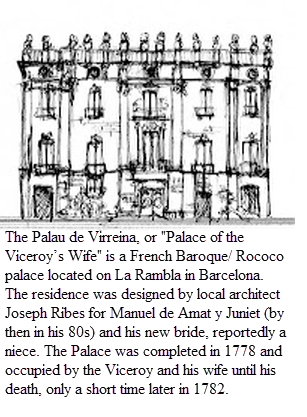

While, far away in Barcelona, her old lover, Amat, had amazed all who yet had any interest in him by the astonishing fact of marrying his niece.

How old was he? Lima computed. Why, he must be nearly eighty. Already it seemed long ago that he had madly loved Micaela. And when he at last died the news was not important to Lima.

For he was become merely a romantic tradition. Then, in his turn, the Viceroy who had succeeded Amat was retired and Ambrose O’Higgins, Marquis of Osorno, took his place.

Micaela could remember that when she was a girl this O’Higgins, a young Irishman, had come to seek his fortune in the New World. He had been just a peddler with a stall in the row of shops under the Cathedral, a stall and a mule, and Riquera, a young Spaniard, for partner. But their business had failed. The young Spaniard had gone back to Spain, and O’Higgins had ridden his mule down into Chile where he had joined the army.

Amat had been Captain-General of Chile at the time, and he had assigned O’Higgins to the task of building stone huts on the east and west approaches to the Pass over the Andes, to serve as shelter for travelers between Mendoza and Chile.

Now the foreign peddler O’Higgins was come back to Lima as a Marquis and the Viceroy of Peru.

How greatly this would have astonished Amat! And Riquera who had been his partner in that shop under the Cathedral had got himself educated and was become Archbishop. They’d been just a couple of itinerant peddlers, and were now the greatest men of all South America, since Lima was the richest and most important city of the continent.

But her own Manuel, who had had every advantage her money could give, was a worthless young sport, hanging forever about the women of the town.

Micaela sent him to Europe in the parental delusion that a far place works miracles, but he returned unaltered and she had later to shut him up in a religious reformatory to prevent his marrying a strumpet, a proceeding which made an unfortunate scandal, for both Manuel and the girl tried to bring legal action against her, as is shown in the archives of Lima. But really Micaela couldn’t let Manuel marry out of his rank like that. After all, as her mother used so often to say, he was the son of a Somebody. It was a duty to Viceroy Amat to get his son properly married.

Micaela was nearly sixty when she herself finally took on the “muy decente” title of Señora, by marrying her fellow-actor, Fermin Vicente de Echarri.

It was toward the end of the century that she entered this epoch of her life, and with her husband signed the lease for a new theater of which together they were to be the managers.

So Micaela’s life flows over into the nineteenth century, the century of South American independence. She was beginning to hear talk of Simon Bolivar and San Martin. People said that Bolivar had freed Venezuela and New Granada from Spain, and that in Buenos Aires and in Chile San Martin had done the same.

Strange talk, that would have seemed insane in the time of Amat! Slaves, too, it was said had been set free. But strangest of all, she, Micaela, had become an old woman. Now after the names of so many that she had known, her mind wrote the words, “ya digunto”

The Viceroy, Amat, now defunct.

Her mother, now defunct.

Then her husband, also defunct.

But the brother Felix — dear faithful Felix — remained.Then — it seemed to have happened all at once — the time came when she was too old to act.

Nothing was now the same, but Felix, and the coach-and-four which she had given to the Parish, still passing on its way to the dying.

This new century seemed to move more quickly than the one in which she’d been born, for as the time shortens it appears unaccountably to speed up. It was hard to believe that Manuel had settled down to a proper marriage and that she had a grand-daughter, grown already to womanhood. Then before Micaela knew where the time had gone she was sending for a notary to draw up her Will:

“In the name of all powerful God, I, doña Micaela Villegas … believing in the mystery of the Holy Trinity … trusting in our Holy Mother, the Apostolic Church, in whose faith I have lived …. Begging the intercession of the most serene Queen of the Angels, Marla, Holy Mother of God, and the intercession of all the Saints of Heaven…

“And because to die is natural, and it must not find me unprepared, I commend my body to the earth and my soul to the most precious Blood, Passion and Death of our Redeemer …. And when I am dead I would be dressed in the habit of the San Franciscans, and have my funeral held in the Church of the Recolecion … but with no more than four candles, for I would give the cost of pomp to the poor ….

“I bequeath to my brother Jose Felix Villegas, for the great love and affection with which he has served me, eight hundred dollars, and a room in my house for the rest of his days ….

“Of what remains, two thirds goes to my son, Manuel de Amat, and a third to his legitimate daughter, doña Tomasa …. With my blessing and the benediction of God ….”

And now all was ready. But there remained yet three months in which life might slowly ebb away:

“Felix, do you remember?…”

“Miquita,I was thinking of the time that —”

Outside, the street cries told off the hours:

The tea-woman-teas for every ill but that final inevitable death, hourly creeping nearer. The flower-man:“A garden! A garden! Muchacha, don’t you smell it?”

Ice cream and wafers rolled thin.

Those who went begging alms for the souls in Purgatory.

Night now, and because of Viceroy Amat, lanterns burning before every door and at the street-corners; Amat the first to give Lima light throughout the night ….

“Felix, do you remember?” …Then the trotting feet of mules, the rattle of the coach. The Sacrament coming in a coach-and-four ….

Why did it rattle like that? …. The coach, too, was getting old. Yes, of course, the coach was old …

Three years later Captain Basil Hall of His British Majesty’s ship, Conway, chanced to be in Lima and saw a “great lumbering old-fashioned coach drive up to the entrance of the Cathedral where it received the priest charged with the Host, and then moved slowly away to the house of some dying person.”

And in answer to his questions he was told that the coach had belonged to a certain Perricholi, a famous actress now dead. It was she who had given the coach to the Parish … Oh, it was a long time ago that she’d given it.

It was a period when women got on with small education; elementary religious instruction and some training in music was thought sufficient. But Micaela’s talent was an impetus to go further. She learned to play with skill on both the harp and the guitar. She had a voice so full of harmony that inevitably she sang to their accompaniment. And her memory was so quick that while she was still a child people were delighted with her recitations. Even as a little girl she could give scenes from the gallant capa y espada dramas, and from the comedies of Lope de Vega, Calderon de la Barca, and Juan de Alarcon.

It was a period when women got on with small education; elementary religious instruction and some training in music was thought sufficient. But Micaela’s talent was an impetus to go further. She learned to play with skill on both the harp and the guitar. She had a voice so full of harmony that inevitably she sang to their accompaniment. And her memory was so quick that while she was still a child people were delighted with her recitations. Even as a little girl she could give scenes from the gallant capa y espada dramas, and from the comedies of Lope de Vega, Calderon de la Barca, and Juan de Alarcon.

And of course her mother, and the brother Felix who all his life adored her, exulted in her instant success. Their Miquita – in the pretty diminutive of intimacy – their Miquita was all at once become the first actress in Lima, to them the first actress in the world. If proof were needed, there was the contract with Maza, impresario of the theater…

And of course her mother, and the brother Felix who all his life adored her, exulted in her instant success. Their Miquita – in the pretty diminutive of intimacy – their Miquita was all at once become the first actress in Lima, to them the first actress in the world. If proof were needed, there was the contract with Maza, impresario of the theater… Now when Lima was not talking of “La Villegas,” as they called Micaela, they were speculating upon what sort of man would be the new Viceroy, expected soon to arrive. The beauty of La Villegas, her latest role, her newest song, alternated with exchange of information about the Viceroy, Don Manuel Amat, who was on his way from Chile.

Now when Lima was not talking of “La Villegas,” as they called Micaela, they were speculating upon what sort of man would be the new Viceroy, expected soon to arrive. The beauty of La Villegas, her latest role, her newest song, alternated with exchange of information about the Viceroy, Don Manuel Amat, who was on his way from Chile. To welcome this new Viceroy, the balconies were hung with banners and tapestries and triumphal arches had been set up along the way by which he was to pass. The cavalry led the procession, followed by the artillery, the city militia and the troops of the line, the university professors in their robes, the members of the audience on horses covered with trappings of black embroidered velvet, the magistrates on foot in scarlet velvet robes, and then the Viceroy. What would he be like, this Don Manuel Amat, who was come to rule Lima?

To welcome this new Viceroy, the balconies were hung with banners and tapestries and triumphal arches had been set up along the way by which he was to pass. The cavalry led the procession, followed by the artillery, the city militia and the troops of the line, the university professors in their robes, the members of the audience on horses covered with trappings of black embroidered velvet, the magistrates on foot in scarlet velvet robes, and then the Viceroy. What would he be like, this Don Manuel Amat, who was come to rule Lima?

His Excellency, Viceroy and Captain General of Peru, President of the Royal Audience, Superintendent of the Royal Finances, Director General of Mines, Knight of the Order of San Juan — It was quite impossible to remember them all. But in a word he was representative of the King himself and responsible only to him. And he loved her Miquita to madness. The whole of Lima knew it.

His Excellency, Viceroy and Captain General of Peru, President of the Royal Audience, Superintendent of the Royal Finances, Director General of Mines, Knight of the Order of San Juan — It was quite impossible to remember them all. But in a word he was representative of the King himself and responsible only to him. And he loved her Miquita to madness. The whole of Lima knew it.

Nothing was now the same, but Felix, and the coach-and-four which she had given to the Parish, still passing on its way to the dying.

Nothing was now the same, but Felix, and the coach-and-four which she had given to the Parish, still passing on its way to the dying. Top Five Wanderlust Wishlist for 2012

Top Five Wanderlust Wishlist for 2012  Happy Easter 2012 from Fertur Peru Travel

Happy Easter 2012 from Fertur Peru Travel  Weather Channel could learn something from the Inca and their descendants

Weather Channel could learn something from the Inca and their descendants  Righteous Pictures Documentary “Web” Coming Soon!

Righteous Pictures Documentary “Web” Coming Soon!  Llama-supported treks coming soon to Peru’s Chaparrí Reserve

Llama-supported treks coming soon to Peru’s Chaparrí Reserve  Peru’s Justice Palace exhibits fake Ricardo Florez paintings – artist’s daughter charges

Peru’s Justice Palace exhibits fake Ricardo Florez paintings – artist’s daughter charges  The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter

The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter  Ollantaytambo: an enduring Inca temple and a Quechua love story

Ollantaytambo: an enduring Inca temple and a Quechua love story