New Study Reshapes Understanding of Moche Chronology

The Moche civilization of ancient Peru, known for its incredible ceramics and monumental architecture, flourished for a much shorter time than previously thought, according to a recent study that upends long-held beliefs about this pre-Inca society.

The study was led by Michele L. Koons from the Denver Museum of Nature & Science and Branden Cesare Rizzuto from the University of Toronto, along with a large international team of archaeologists from the United States, Canada, Peru, and Japan.

The researchers partnered with multiple universities and institutions, including Columbia University, the University of California, Santa Barbara, the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, and the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Shorter Civilization Span

For decades, archaeologists relied on ceramic styles to trace the timeline of Moche culture, which was believed to have thrived for nearly a millennium.

However, the study’s Bayesian analysis, which aggregates and assesses radiocarbon dates from the broad field of Moche archaeological sites, paints a different, more complete picture.

When did the Moche civilization begin and end?

The Moche civilization, long believed to have lasted from around 1 CE to 800 CE, likely began much later— between the 4th and 6th centuries — and ended in the 9th century, the study claims.

Radiocarbon dating methods, applied to both organic material and ceramics, show clear overlap of the Moche’s time frame with other prominent Andean cultures like the Wari and Tiwanaku.

The Role of Ceramics in Dating

Archaeologists traditionally used pottery patterns and styles to estimate the timeline of the Moche culture and where their excavation fit in the chronology.

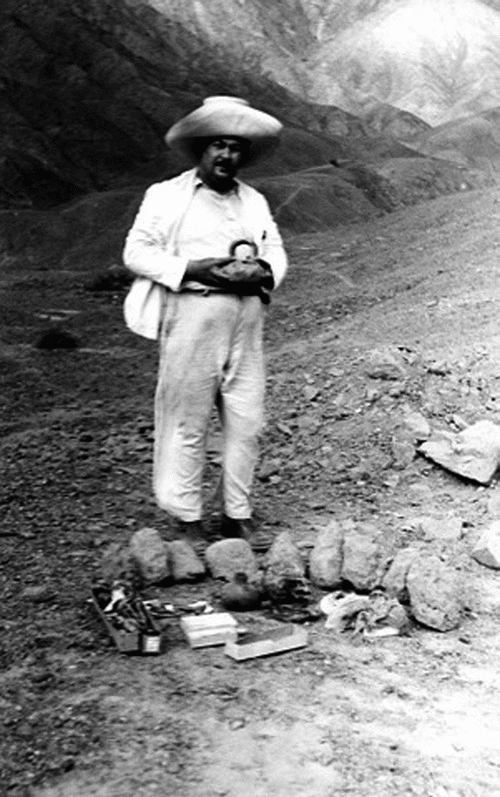

Peruvian Archaeological Pioneer Rafael Larco Hoyle

The foundational method for understanding Moche ceramics was pioneered in 1946 by Peruvian archaeologist Rafael Larco Hoyle.

That was the same year that radiocarbon dating was first invented by Willard Libby and his colleagues at the University of Chicago.

But it would be decades before advances in radiocarbon dating were available in archaeology.

So Larco drew on his family’s background in Peruvian agriculture to forge his own ingenious and innovative approach to date Moche artifacts.

The pottery, or huacas, that Larco excavated came primarily from the Moche and Chicama Valleys.

Larco observed that El Niño and La Niña weather patterns left distinct layers in the soil. El Niño events brought heavy rains and flooding, depositing thick layers of sediment, while La Niña periods were marked by drier conditions and thinner layers.

Estimating the frequency of these events, Larco calculated the age of the artifacts based on their depth in the ground in relation to the sediment layers.

Then he categorized the Moche ceramics, noting the variations in the designs of the stirrup spouts. He further considered factors like the handle and spout shapes, the rim designs, vessel body proportions, paint type, and sculptural details.

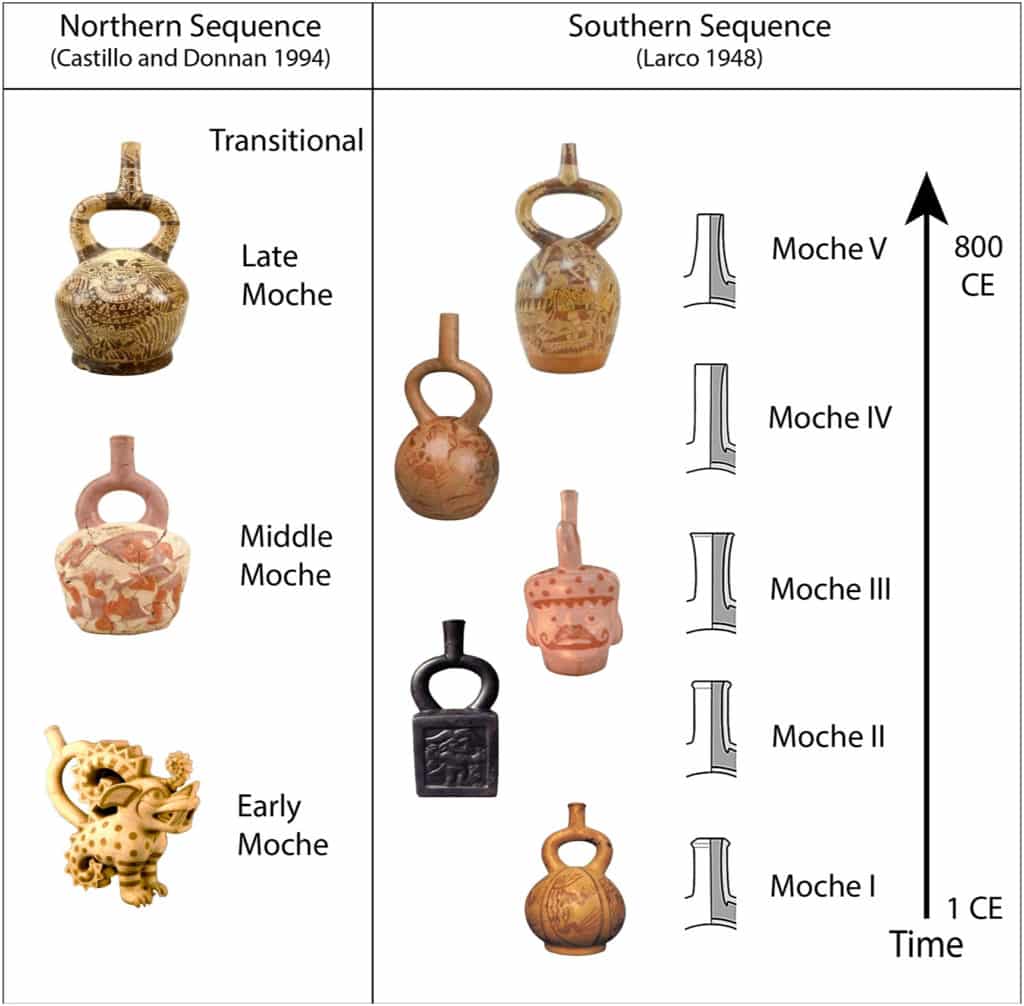

Larco concluded that the Moche ceramics fit into five discernible phases (Moche I-V). This breakthrough theory suggested a specific spread of ceramic styles that he, and subsequent generations of archaeologists, extrapolated to track Moche territorial expansion.

Archaeologists Challenge Larco’s Framework

But then, in 1994, archaeologists Christopher Donnan and Jaime Luis Castillo put radiocarbon dating to use. They tried to fine-tune Larco’s influential five-phase ceramic sequence and found the chronology just didn’t quite fit.

Larco’s theories were primarily based on data from the southern Moche heartland. His framework didn’t match the northern Moche regions where Donnan and Castillo were excavating.

Donnan and Castillo argued that the northern Moche region corresponded not to five, but rather three main phases: Early Moche, Middle Moche, and Late Moche.

They theorized that the northern and southern Moche regions, even though they had some similar cultural traits, were related, yet separate societies.

These subtle differences between the northern and southern Moche sectors — with regard to the ceramics, social organization, and religious practices — demonstrated a need to reevaluate aspects of Moche culture that Larco’s model left unexplained.

New Analysis Reveals Overlapping Styles

The new Bayesian analysis takes this differentiation to a whole other level, challenging the very idea of linear progressions in ceramic styles. It reveals significant overlap between phases and suggests that the different styles weren’t produced as uniformly or orderly as previously believed.

The Bayesian statistical modeling refines chronological estimates by integrating radiocarbon dates from diverse Moche ruins and cross-referencing them with the different ceramics.

For example, ceramics identified as Moche I and II are so similar that they should be collapsed categorized into one style, the study argues, while Moche III-IV ceramics show overlap across various regions.

Radiocarbon Dating Revolution

In other words, the radiocarbon revolution of the mid-20th century has come of age in Peruvian archaeology and is now transforming research with absolute dating of organic material.

Geographical Variation in Moche Culture

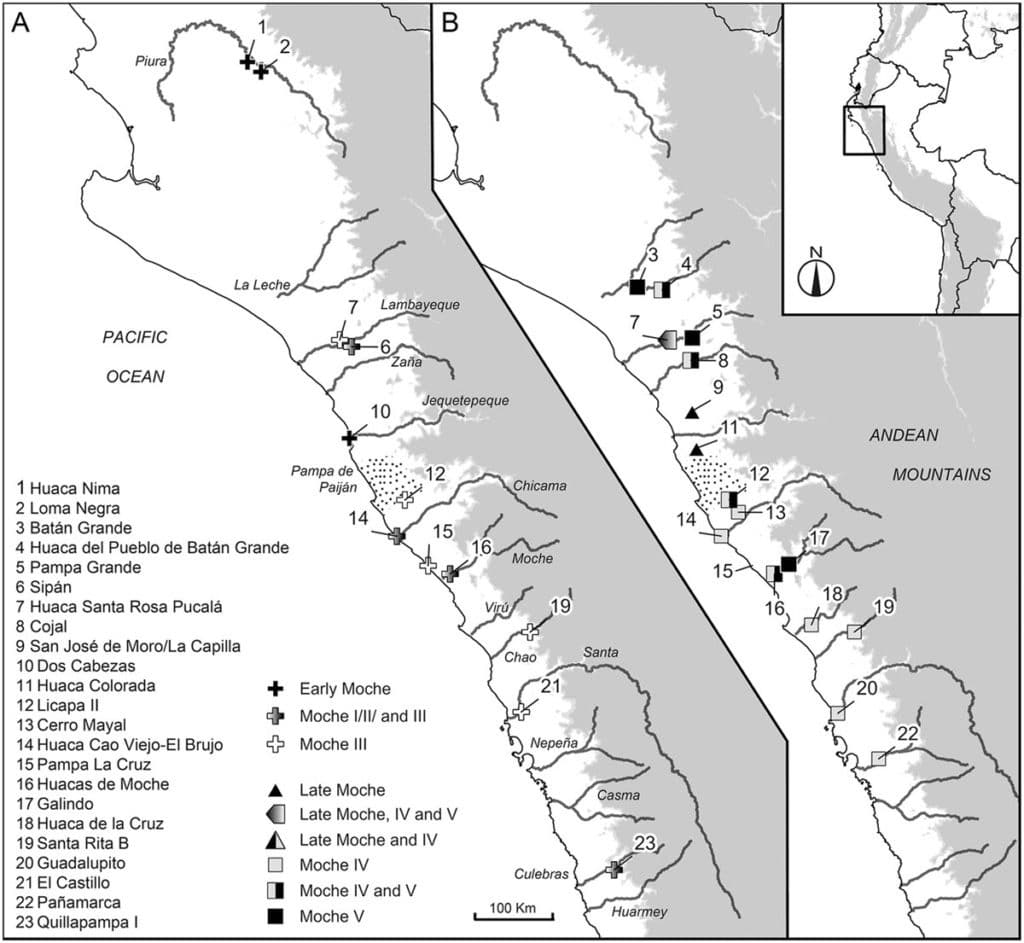

By evaluating 410 radiocarbon dates from 26 Moche sites, the researchers built a comprehensive database of dates tied to specific ceramic styles.

The analysis pinpoints certain Moche ceramics that do not align with previously accepted time-frames. Some of the conclusions are granular. For instance, the onset of the Moche III phase appears to have been delayed by up to 100 years in some regions, but not others.

Challenging the idea of the Moche as a single unified state

These radiocarbon dates reveal a far more complex political landscape, based on the regional variations in ceramics and cultural practices. The earliest estimates of when Moche civilization began was roughly 300-500s CE and it ended in 800s CE.

Significant Findings from Key Sites:

- For example, Huacas de Moche, home to the famous Huaca de la Luna temple complex, produced more than 100 radiocarbon dates that confirm the site was occupied well into the 9th century. That challenges earlier assumptions that it was abandoned around 600 CE.

- Northern sites show evidence of cultural mixing. At Huaca Santa Rosa de Pucalá and San José de Moro, archaeologists found pottery that combines Moche and Wari artistic styles, suggesting the two cultures interacted more than previously thought.

- At Sipán, famous for its royal tomb containing one of the richest collections of ancient American gold ever found, new dates suggest the site was occupied much later than archaeologists once believed, most likely from 635 to 745 CE

- In contrast are southern sites like El Brujo archaeological complex has yielded some of the earliest known Moche pottery styles. It is home to the Huaca Cao temple where the tattooed mummy of the Lady of Cao was discovered. Archaeologists consider her the earliest known female ruler in pre-Columbian Peru, drawing comparisons to Cleopatra of ancient Egypt.

Implications for Moche Studies

This study’s authors urge the archaeological community to reconsider long-standing theories about Moche political organization and expansion.

As more radiocarbon dates become available and Bayesian methods evolve, the story of the Moche will continue to be revealed.

Thank you María Rostworowski on your birthday for a lifetime of work bringing Peruvian history to life

Thank you María Rostworowski on your birthday for a lifetime of work bringing Peruvian history to life  Girl Power in Colonial Peru: Santa Rosa of Lima Backstory

Girl Power in Colonial Peru: Santa Rosa of Lima Backstory  Pisco Sour History 101 Questioned

Pisco Sour History 101 Questioned  The History of Surfing in Peru

The History of Surfing in Peru  The Inca Sun of Suns Could be Returned to Cusco – by Donald Trump?

The Inca Sun of Suns Could be Returned to Cusco – by Donald Trump?  Alternative Lima Tour: Royal Felipe Fortress

Alternative Lima Tour: Royal Felipe Fortress  Peruvian Pisco’s 400-year history on exhibit in historic Lima

Peruvian Pisco’s 400-year history on exhibit in historic Lima  The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter

The Inca Sacred Center of Machu Picchu – a Love Letter