Throne Room of Female Moche Ruler Uncovered in Northern Peru

A stunning new discovery at Pañamarca, an ancient Moche site in northern Peru, has revealed a throne room that was likely used by a powerful female leader.

This groundbreaking find, made in July during excavations at Pañamarca in Ancash, is just the latest proof that women held significant religious and political roles in Moche society.

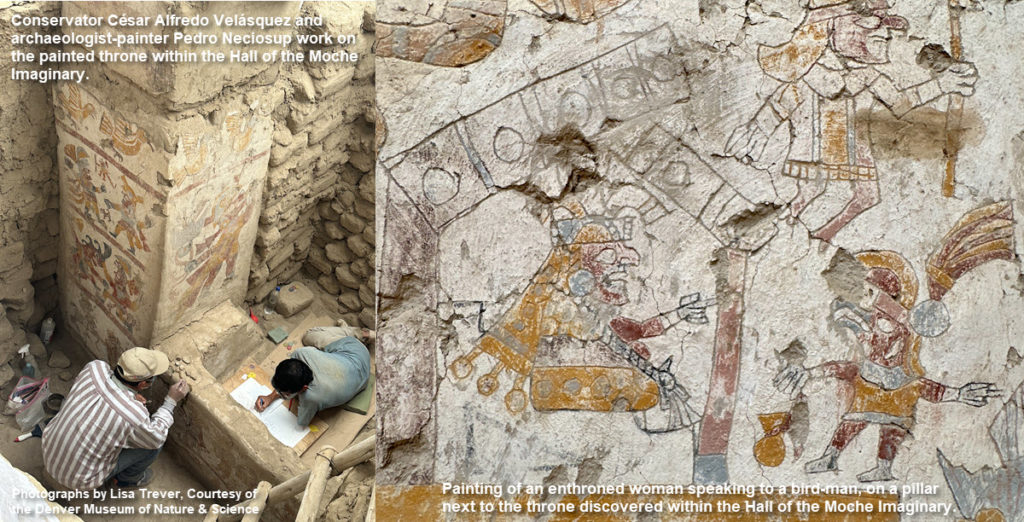

The research team, a collaboration of Peruvian and U.S. archaeologists, conservators, and art historians, discovered the adobe throne within a painted hall they’ve dubbed the “Hall of the Moche Imaginary.”

This discovery represents the first known throne room for a female leader in Moche history, according to the researchers.

The project is funded by the National Geographic Society, the Institute of Latin American Studies at Columbia University, and the Avenir Conservation Center at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

A Glimpse into Moche Civilization

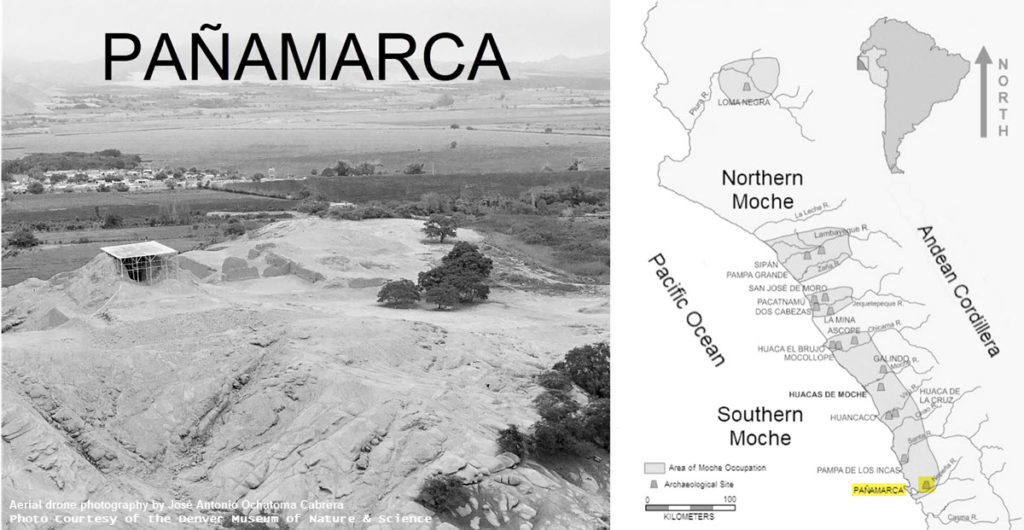

Pañamarca, located in the Nepeña Valley, is the southernmost monumental center of the Moche culture, which flourished in northern coastal Peru from around 300 C.E.

Artistically, the Moche were arguably the most remarkable ancient civilization of the Americas.

Moche artisans meticulously captured their culture, religion, architecture, and agriculture, as well as their wars, ceremonies, burials, medicine and sexuality, through vibrant murals and highly realistic fired-clay artifacts.

“What followed during about 600 – 850 or so could even be considered a ‘renaissance’ given the astonishing accomplishments that took place,” Lisa Trever, professor of Art History at Columbia University, tells us. “Our radiocarbon dates for the Moche period at Pañamarca are all falling between 550 and about 800.”

The site, known for its brightly colored murals, has long captivated archaeologists going back to the 1950s. Previous finds included mural paintings of priests, warriors, and supernatural beings in vibrant processions. In 2010, a Moche feathered shield was discovered.

However, this newly discovered throne room stands out as the latest evidence of a high-status female leader in Moche history.

The find is no anomaly.

Excavations at San Jose de Moro between 1991 and 2013 unearthed eight elite female Moche mummies, including a 1,200-year-old high priestess.

“Our excavations have only turned up tombs with women, never men,” archaeologist Luis Jaime Castillo, project director of San José de Moro, told Agence France-Presse in 2013. The discovery of the last tomb, he said, “makes it clear that women didn’t just run rituals in this area but governed here and were queens of Mochica society.”

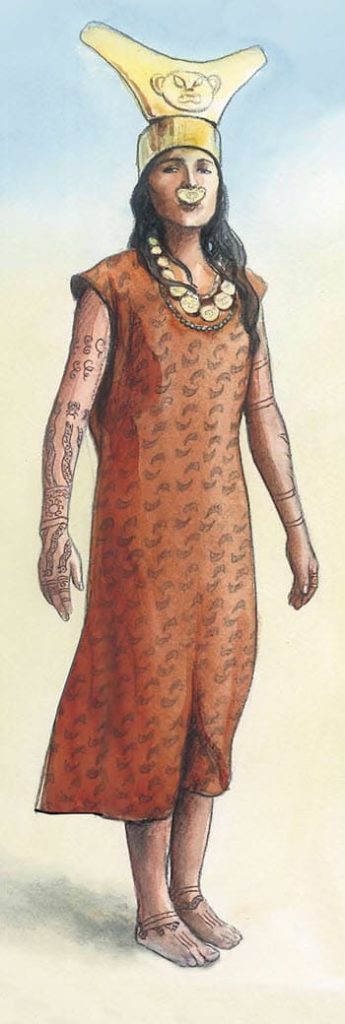

In 2005, archaeologist Regulo Franco unearthed the intact tomb of a young woman now known as the Lady Cao at the El Brujo archaeological complex.

The woman’s body, adorned with snake and spider tattoos, was found with ornate regalia typically associated with high-ranking Moche leaders. Experts believe the tattoos symbolized mystical powers attributed to her by her people.

Lady Cao, who lived around 400 C.E., is thought to have died shortly after childbirth. Archaeologists consider her the earliest known female ruler in pre-Columbian Peru, drawing comparisons to Cleopatra of ancient Egypt.

“The Lady Cao was a ruler, whose tattooed body was a living oracle,” said Franco, who went on to run operations at Machu Picchu. He recently was appointed director of the Ministry of Culture’s Cusco Directorate.

“She wasn’t a priestess either,” Franco told Peru daily La República for an interview commemorating the 15th anniversary of the Dama Cao’s discovery. “She was a woman with political power.”

The adobe throne discovered in Pañamarca suggests that a female leader wielded significant power there as well during the seventh century.

The throne is decorated with murals depicting a powerful woman associated with the crescent moon, the sea, and weaving. Some scenes show her receiving visitors, while others portray her seated on the throne, surrounded by murals of other women spinning and weaving textiles.

Moreover, the researchers say the throne showed signs of wear, particularly erosion on the backrest. This, combined with the discovery of fine threads, greenstone beads, and human hair at the site, suggests the throne was not merely symbolic but actively used.

“Pañamarca continues to surprise us,” says Trever, “not only because of the inexhaustible creativity of its painters, but also because their works are changing our expectations about gender roles in the ancient Moche world.”

Unearthed Murals Show Creative Mastery

Murals surrounding the throne in the Hall of the Moche Imaginary display rich scenes of Moche life and mythology.

The painted pillars depict the powerful female figure in scenes of authority and procession. Intricate images of women spinning and weaving in a large workshop were also uncovered, along with depictions of men carrying textiles and the leader’s crown, braided with her hair.

The Hall of the Braided Serpents: A Monumental Discovery

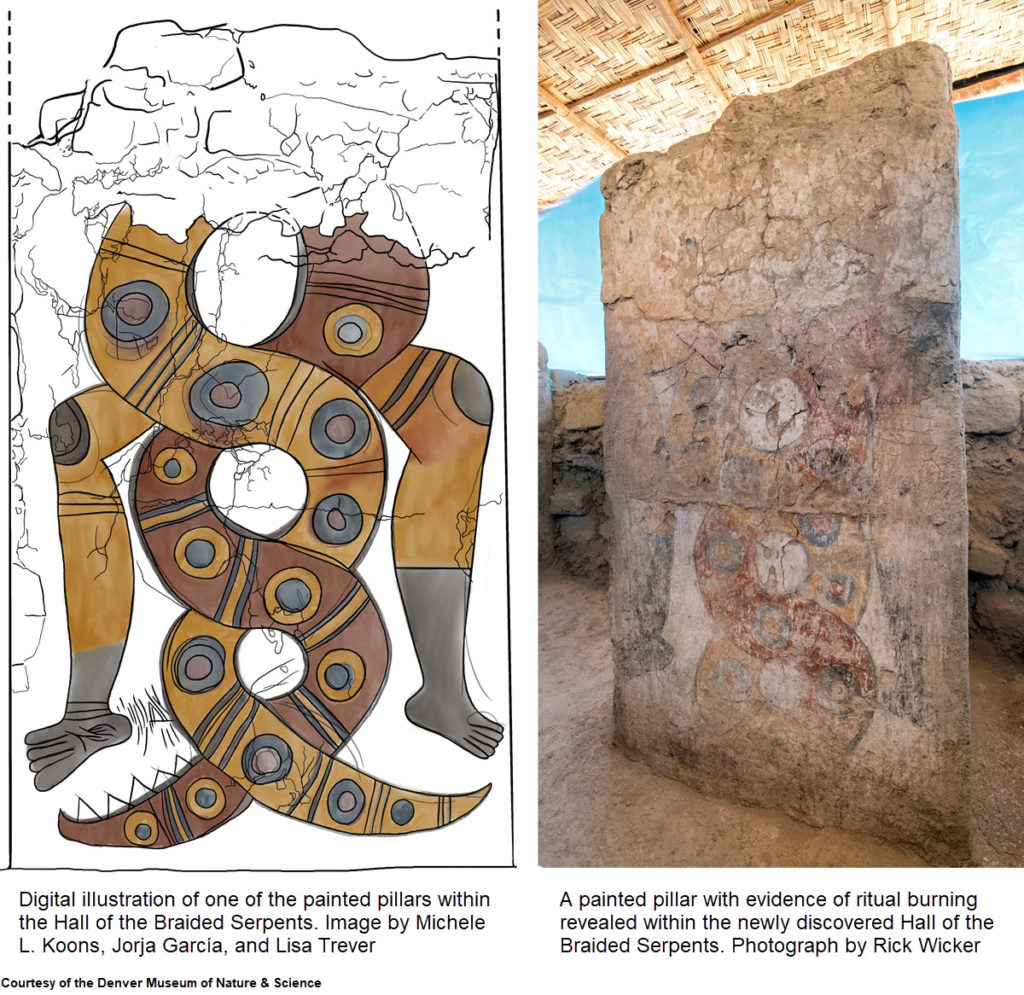

Alongside the throne room, another significant find emerged from the ongoing excavations. The “Hall of the Braided Serpents” is a newly discovered structure on Pañamarca’s plaza. This hall features wide square pillars painted with intertwining serpents — a motif not seen in other Moche art. Other murals show warriors, anthropomorphic weapons, and a monstrous figure chasing a man.

The hall appears to have been an elite space, likely used for rituals and gatherings. Archaeologist Michele L. Koons of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science says the hall’s strategic position is “almost like the boxes of a theater or stadium from which to observe what was happening below, while providing private spaces for its privileged occupants.”

Excavations show that the hall underwent several renovation phases, including the burning of offerings and the whitewashing of murals. These events, along with the unique serpentine imagery, suggest it was a significant ceremonial space in the Moche world.

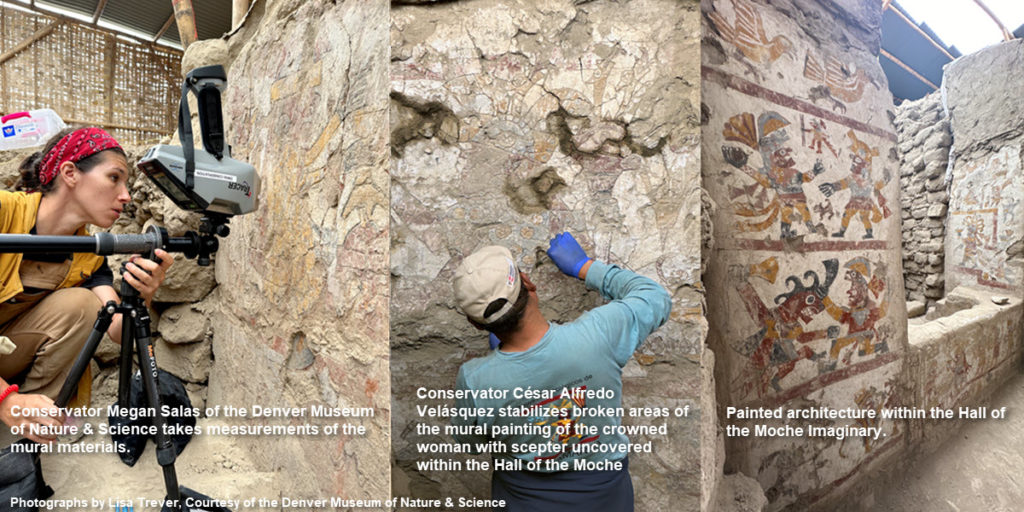

Conservation Efforts and Digital Preservation

The murals at Pañamarca are extremely fragile, and conservation is a top priority. The research team is working with local and international experts to stabilize and protect the newly uncovered murals.

Using traditional techniques alongside modern digital technology, they are meticulously documenting every detail of the paintings to ensure future access for both scholars and the public.

Without proper conservation, these murals would quickly degrade, says archaeologist José Antonio Ochatoma Cabrera. “That’s why we cover the murals at the end of each field season to protect them from the elements.”

The team is also investing in protective structures, such as roofs and windbreaks, to safeguard the murals. In addition, they are creating detailed digital renderings of the site, which will be accessible through various online platforms.

“We want to make sure this heritage is preserved for future generations, both physically and digitally,” says Ortiz Zevallos.

The Future of Pañamarca

While tourism to Pañamarca is currently restricted due to the fragility of the murals, future efforts may allow for limited public access, once conservation infrastructure is fully in place.

“If left exposed to the elements without an on-site permanent conservation program, Pañamarca’s invaluable murals would begin to deteriorate immediately,” says Ochatoma Cabrera.

That’s what happened to murals first discovered in the 1950s, he added. “We cover the excavations to ensure long-term conservation of this important cultural heritage.”

The spiritual afterlife of dogs in Peru

The spiritual afterlife of dogs in Peru  Peru government takes action to reopen old and new routes to Machu Picchu within 8 weeks

Peru government takes action to reopen old and new routes to Machu Picchu within 8 weeks  Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum

Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum  Vilca Lords and the Lord of Wari on exhibit in Cusco

Vilca Lords and the Lord of Wari on exhibit in Cusco  Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking

Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking  Peru’s plan to invest upwards of $417 million to build the Moche Trail

Peru’s plan to invest upwards of $417 million to build the Moche Trail

Hello Rick

I loved your blog. It’s very interesting and more importantly, based on archeological evidence.

I will probably use some of them in my lessons!

Love the boys an Siduith!

Thank you Martha! It’s an honor.