Want to know a Real Indiana Jones? Tomb Raiding Tales of Peter O’Toole

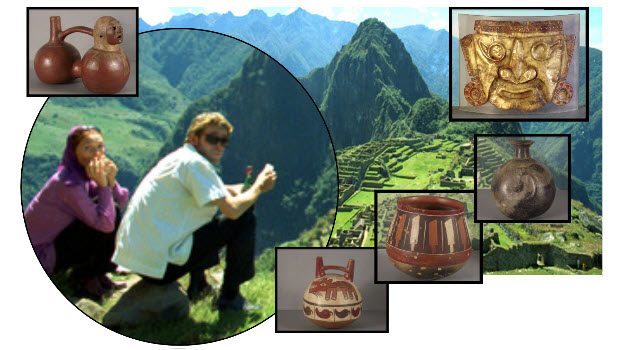

So who was the real Indiana Jones? Most point to Hiram Bingham, the scientific “discoverer” of Machu Picchu. Many more say Hollywood’s most beloved tomb raider was actually an amalgamation of that real-life Yale University explorer and Harry Steele, the harder boiled, treasure hunting protagonist from Secret of the Incas, a 1954 B-movie classic shot on location in Cusco.

Here’s another suspect. It’s someone as legendary as Harrison Ford and twice the actor that Charlton Heston ever was. And three times as roguish, as well: Peter O’Toole.

Yes, Peter O’Toole, who died in 2013, and who is perhaps best known for his role as Lawrence of Arabia in the David Lean film of 1962.

He never donned the iconic fedora and brown leather jacket on the big screen. No bull-whip. But between Oscar nominations for his portrayals of an ego-maniacal and spiritually damaged T.E. Laurence and the swashbuckling, redemptive drunk Alan Swann, Peter O’Toole played a real-life role, fervidly looting ancient tombs.

Peter O’Toole’s Tomb-Raiding Exploits

“O’Toole’s passion for archaeology and collecting antiquities began on Lawrence of Arabia, and was happily satisfied with each new far-flung location,” writes Robert Sellers in Peter O’Toole: The Definitive Biography. “Dotted around the house were Noh masks from Japan, a bejeweled Persian chest and his particular favorite — pre-Columbian art.”

The lengths to which O’Toole would go for his “collecting” activities was quite astonishing.

“He once confided to the photographer Bob Willoughby that he smuggled a pair of precious Greek earrings through customs by hiding them in his foreskin, resulting in some minor discomfort that lasted weeks,” Sellers reveals.

“Going off on excavation digs, O’Toole explained to Malcolm McDowell on the set of Caligula that the best way to find Etruscan jewelry was to locate the drains in the tombs, and then to sift through all the grime with one’s fingers because as the bodies decompose all the artifacts deposit themselves into the channels: ‘The thought of Peter O’Toole on his hands and knees in an Etruscan catacomb makes for a lovely image.’”

O’Toole lavished much of the ancient loot on his former wife, actress Siân Phillips, who immortalized their travel adventures 24 years after their divorce, and a decade before his death, in her memoir, Public Places: My Life in the Theater, with Peter O’Toole and Beyond.

A big chunk of Phillips’ reminiscences focus on their escapades with American photographer Bob Willoughby after location filming of Murphy’s Law in 1970 in the Venezuelan jungle. Always referring to her husband of 20 years as “O’Toole” or simply “the Irishman,” Phillips lyrically describes dense, mist shrouded rain forest and “massive, squat, sheersided, table-top mountains that seem to belong in a work of fantastic fiction.”

She, Willoughby and O’Toole spent days with a Yanomama tribe. They made a death-defying helicopter journey to the apex of Angel Falls, “setting down on a piece of flat ground” that to Phillips’ “fevered, disturbed senses” didn’t “seem to be much bigger than a grand piano.” And they spent a night in the remote cabin of a shot-gun toting expatriate explorer called “Jungle Rudi” who “talked on and on, directing his attention to O’Toole only, speaking in an urgent, low monotone.”¹

The adventure was supposed to end with a flight back to Caracas aboard a Cessna, but that was cut short by a violent storm and a forced emergency landing on a remote field.

“The pilot managed to land and we stood in the middle of nowhere with our bits of luggage — mainly Bob’s equipment — until the pilot succeeded in raising a local taxi who was startled but game when we asked him to drive to Caracas, five or six hours away. Bob and O’Toole pressed a great deal of money into the pilot’s hand and off we lurched” all the way to the luxury Hilton Hotel.

Visiting Machu Picchu: The Journey Fueled by Rogue Spirit

From there, Phillips and O’Toole had planned to return home to England, but Willoughby’s wife, Dorothy had been waiting for him at the Hilton:

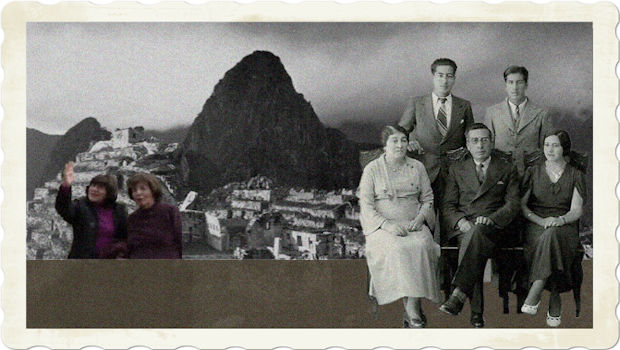

“‘We’re going to Machu Picchu,’ they said. ‘Not without us,’ said O’Toole and I went upstairs to pack and change the air tickets and telegraph London to say that we were safe and almost on the way home.”

They rendezvoused with their friends in Cusco and “obediently followed all the rules for acclimatizing to this altitude; no alcohol and a four-hour sleep, then very slow movement for a while.”

Like all the visitors, she wrote, they wanted to go to Machu Picchu.

“In 1970 it was still an uncomfortable trip and along with a cartload of other tourists we felt slightly adventurous,” Phillips remembered. “There was no place to stay, it was a bit like going to Petra ten years previously, and we were well able to rest curled up under a rock. Nothing can prepare one for Machu Picchu and nothing one can say can add to the descriptions or convey the wonder of it.”

A Mysterious Night-Time Pickup: O’Toole’s Risky Acquisition

Their night before heading back to London, O’Toole made a mysterious night-time pickup. Phillips’ account about the event is excerpted here:

We moved on to Lima where O’Toole had a contact in the art world. Bob and his wife left us after the one conventional meal we were to enjoy and they also gave us money; we had run out but there was something called a credit card and it gave you money, no matter where you were. O’Toole and I were mystified and impressed and grateful. Lima was the noisiest city I had ever been in – or was I now unused to urban din? O’Toole went off to ‘meet a man — don’t ask’ and I ‘Wait here’.

To pass the time, I pressed my dried plants (my mother would be fascinated to see them) and repacked our luggage and sat looking at the dark street. This city scared me somewhat, though I didn’t know why. At four in the morning O’Toole returned, exhausted, bearing a few plastic shopping bags. ‘Pack these — don’t look. God, I’m tired.’

Fully clothed, he stretched out on the bed and slept. This man slept better and longer than anyone I knew. Dutifully, I didn’t ‘look’ and I packed the objects in the luggage. When O’Toole woke, we left for the airport and home.

In Bogota we landed unexpectedly and the plane was kept on the ground for hours. ‘Sorry, love,’ he said. ‘I think the game’s up. Don’t forget you really don’t know what’s in those bags.’ I tried to read and not contemplate the punishment for the unlawful liberating of works of art. Suddenly we were off!

I couldn’t look at him. It was the luck of the Irish, dammit. I felt sick.

In the Green Room of Guyon House, my mother and Kate and Pat and Liz and Manolita unpack and drink tea. ‘Oh, thank God for a decent cup of tea,’ groans the Irishman. ‘Where’s the jewelry?’ ‘What jewelry?’ ‘You know – the jewelry from Lima.’ ‘Was there any? You said not to look.’ ‘Oh Jaysus — I’m surrounded by eejits.’

‘Wait, wait,’ soothes my mother and goes to search through the rubbish. ‘Is this what you were looking for?’ she says, holding up a ratty plastic shopping bag. ‘Could be,’ and he drops the most beautiful old necklaces over my head. The Pre-Columbian masks are put aside to be sent to our British Museum friend who will ‘blow’ the flattened gold back into shape and then they will be sent to Claude de Muzac in Paris to be mounted. We all look at the beautiful, battered, soft gold faces. The girls stroke them and I can’t feel too guilty about any of this.

—Public Places: My Life in the Theater, with Peter O’Toole and Beyond (May 29, 2003)

by Siân Phillips

Ill-Gotten Antiquities Revealed: Peter O’Toole’s World Class Collection

In May 2017, that collection went on sale. The Gallery catalog displayed dozens of antiquities — Roman, Persian, Chinese and especially pre-Columbian artifacts, including Maya and Aztec pieces from Mexico and Central America; a gold Calima Gold Crown from Colombia…

And from Peru: Moche, Chimu and Nazca pottery and a hammered gold alloy Sicán mask, blown into shape and beautifully mounted on a curved Plexiglas display.

The treasure trove of ancient artifacts and cultural patrimony

Peter O’Toole always was, and always will be, one of my all-time favorite actors. It would be nice, though, if that mask and the other relics — all cultural patrimony — that he “liberated” in 1970 were repatriated to the rightful owners, the people of Peru.

Sicán Gold Mask.

Hammered sheet gold alloy in relief with traces of red pigment.

Sicán culture, North Coast Peru. Circa 700-1200 A.D.

Price £6,000.00

¹This cursory citation does not do justice to Phillips’ mood-inducing description of “Jungle Rudy.” Rudolf Truffino Van Der Lugt was a Dutch adventurer who could very well have been portrayed by O’Toole on the big screen. He was ruggedly handsome. He successfully explored uncharted swaths of seemingly impenetrable Venezuelan jungle. He started a family, homesteading in the remote shadow of Angel Falls, and built a rustic lodge for a mix of jetsetters and pioneering explorers. Beset by personal demons, Jungle Rudy died in 1994 on a hammock, alone, abandoned by his three daughters — broken and friendless.

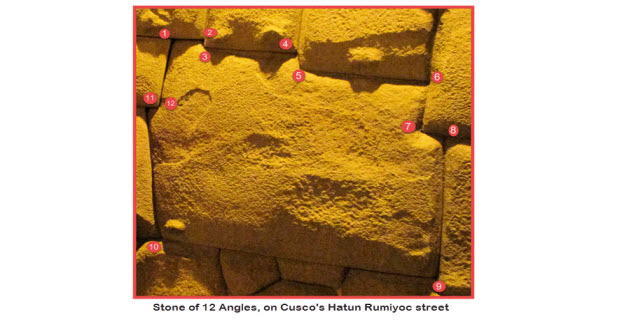

Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone

Famous 12 angle Inca stone topped but not overshadowed by 13 angle stone  The Bad Intentions to vie for foreign language Oscar

The Bad Intentions to vie for foreign language Oscar  The History of Surfing in Peru

The History of Surfing in Peru  Airlines to Peru and the runways of aviation history: Peruvian airport names

Airlines to Peru and the runways of aviation history: Peruvian airport names  Pisco Sour History 101 Questioned

Pisco Sour History 101 Questioned  How the mystery of Francisco Pizarro was solved

How the mystery of Francisco Pizarro was solved  Why did Peru’s most famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa punch his best friend Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the face?

Why did Peru’s most famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa punch his best friend Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the face?  Disputed landladies of Machu Picchu seek humongous back rent

Disputed landladies of Machu Picchu seek humongous back rent