Incas Learned Seismic Lesson From Machu Picchu Earthquake

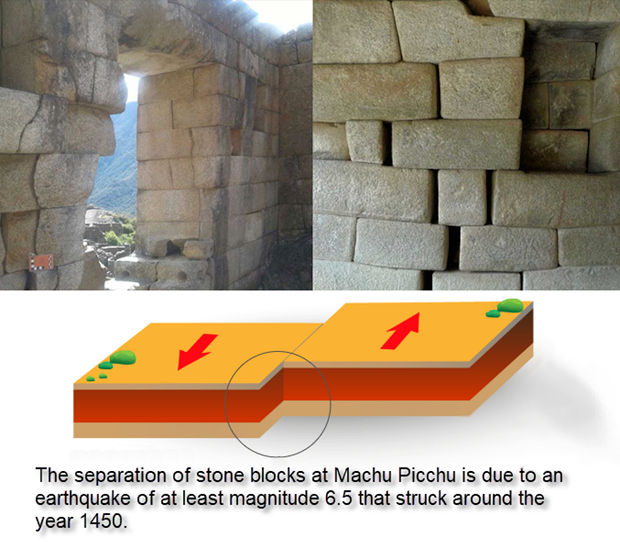

[Originally published December 13, 2018] In the midst of its construction, Machu Picchu was rattled by a powerful earthquake around 1450, forcing the Inca to rethink and improve their seismic-resistant building techniques, according to a new study.

The temblor, which registered at least a magnitude 6.5 or greater, knocked loose the stone blocks of the Temple of the Sun and caused still-evident damage to the mason walls throughout the ceremonial centers of Machu Picchu, according to the Cusco-Pata Research Project.

The project, spearheaded over the last two years by Peru’s Geological, Mining and Metallurgical Institute, got a major Spanish-language write-up on the state-run news agency Andina Website.

The Inca Empire’s greatest ruler Pachacutec was in the middle having Machu Picchu built as a royal summer getaway retreat when the quake hit, says the project coordinator Carlos Benavente Escobar.

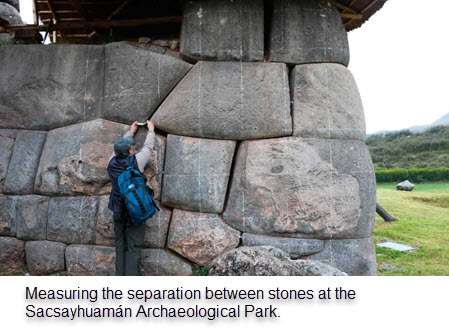

“After that, they continued the building in a different manner to complete what would become Machu Picchu,” Benevente told Andina. “There is no doubt,” he added, that the strong earthquake also caused the deformation of the walls at Sacsayhuamán, Tipón and Tambomachay, as well as along the street of the Twelve Angles Stone in the city of Cusco, among other areas.

From that point forward, the Inca moved away from using smaller stones, assembled in a more rustic cellular architecture, and instead developed and perfected the construction of seismic-resistant trapezoidal structures that remain throughout the Cusco region today, with giant stone blocks at the base and narrower, inward inclined upper walls.

“They knew how to coexist with diverse geologic dangers, like earthquakes, landslides and avalanches,” Benavente said.

He said the study, which reportedly will continue into 2019, will provide a clearer picture of the seismic hazards of the Tambomachay and Pachatusan fault lines and help the Cusco region to not only preserve its Inca heritage sites but also aide urban planners make Cusco safer for the future.

“For the first time in history, the techniques of paleosismology, archaeo-seismology and active tectonics have been combined in a study of this nature,” Benavente said.

The study reveals just how complex the Inca’s understanding telluric movements was, which allowed them to engineer vast agricultural terraces on steep mountainsides with sufficient yields to feed an empire.

The Inca’s largest expansion in the Cusco region occurred on the left bank of the Huatanay River, precisely where the Tambomachay fault is located — begging the question, why build there, despite the risk?

The answer, Benavente says, is simple. The geological fissures are a major conduit of water.

“The Incas wanted water; therefore, they preferred to improve the structural conditions of their homes rather than move away from the water resource,” Benavente said.

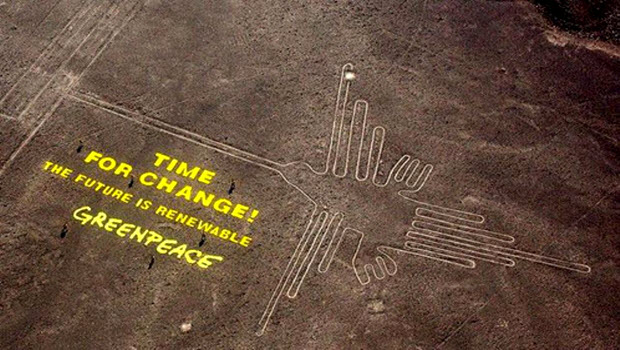

Greenpeace activists in hot water over Nasca Lines act

Greenpeace activists in hot water over Nasca Lines act  Restoring the Inca ecological balance at Sacsayhuaman

Restoring the Inca ecological balance at Sacsayhuaman  Peru Scrabble® Tour & Tournament Oct. 4 – 12, 2013

Peru Scrabble® Tour & Tournament Oct. 4 – 12, 2013  What Cusco tours could look like in 2025

What Cusco tours could look like in 2025  Arequipa tour attraction Juanita mummy placed in deep freeze

Arequipa tour attraction Juanita mummy placed in deep freeze  All Arts Festival underway in hommage to Arguedas

All Arts Festival underway in hommage to Arguedas  Cable Car Connecting Sacred Valley And Huchuy Qosqo Approved By Peru Tourism Ministry

Cable Car Connecting Sacred Valley And Huchuy Qosqo Approved By Peru Tourism Ministry  Machu Picchu offers a lesson of spirituality, resilience & beauty, says IMF chief

Machu Picchu offers a lesson of spirituality, resilience & beauty, says IMF chief