Ollantaytambo: an enduring Inca temple and a Quechua love story

☼ Inca Tours and Romantic Vacations ☼

Ollantaytambo is a town located at the end of the Sacred Valley along the Urubamba River, roughly 37 miles (60 kms) northwest of Cusco.

One of the longest continually inhabited towns in the Americas, Ollantaytambo was constructed at the foot of a spectacular Inca ruins. Thousands of travelers make the journey through the Sacred Valley each day to climb its 17 agricultural terraces leading steeply up the side of a hill to a massive stone Sun Temple.

The ruins are referred to as a fortress, garden citadel. It’s construction is attributed to the 9th Sapa Inca Pachacutec, who conquered the territory and then built the town and temple as one of his royal estates.

The complex still has extensive, functioning Inca waterworks, including a fountain at the base of the ruins, known as “The bath of the princess.”

The name of the town and its megalithic archaeological ruins are also associated with something else: a pre-Columbian story of tragic romantic drama. It’s something that doesn’t always get mentioned on the guided tours, but according to legend, Ollantay was a valiant warrior chief and Pachacutec’s most trusted general.

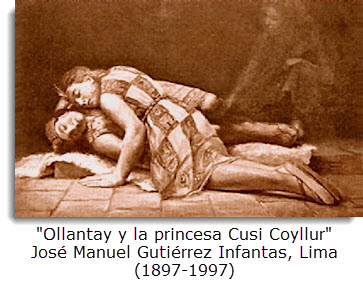

The relationship soured, however, when Ollantay and the Inca emperor’s daughter, Cusi Coyllur, fell in love.

Since Ollantay was not of royal blood, the pair carried on their forbidden love affair in secret and she soon was carrying his child.

Ollantay appeared before the Inca and asked for the princess in marriage. But Pachacutec refused. He angrily dismissed Ollantay and banished his daughter to the Convent of the Virgins of the Sun.

With his suit for Cusi Coyllur’s hand scornfully rejected, Ollantay climbed the dizzying mountain heights overlooking Cusco and in a powerful soliloquy declared himself the implacable enemy of the empire.

The original story builds in sonorous, rhythmic Quechua into an epoch tale of treachery, defeat, mercy and finally absolution.

Ollantay is pardoned, and reunited with his beloved Cusi Coyllur, as well as their 10-year-old daughter, Yma Sumac.

Is the story truly of Inca origin? According to an academic article written by Michael V. Karnis in the Educational Theatre Journal in 1952, yes, it is.

Chroniclers like Garcilaso de la Vega and Cieza de León, wrote that histories, love songs and elegies were performed before the Inca court. Many 19th and 20th centuries scholars argued that the story of Ollantay has its origins in that tradition.

Despite orders prohibiting the presentation by indigenous people of any drama celebrating heroic feats of the Inca royalty, this centuries old tale survived — past down in oral tradition in the ancient Inca language, accompanied by elaborate music and dance.

The first modern mention the Ollantay drama came in 1835, when Manuel Palacios published an academic article about it in Cusco.

But it was not until 18 years later that the German explorer and linguist J.J. von Tschudi published a translation, and Ollanta started to gain world attention. He copied his manuscript from one preserved in the Dominican monastery at Cusco.

Clements Markham, the indefatigable English scholar and explorer, got his hands on an older manuscript of the play and in 1871 published his attempt at a literal English translation.

Ten years after that, former Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre wrote an essay asserting that Ollantay was not of Inca origin, but in fact was written in comparatively modern times. That set off a 60-year, international debate, the notoriety of which resulted in the play being translated into not only Spanish, English, and German, but also French, Italian, Czech, and Latin, as well.

Ernst Wilhelm Middendorf, a German anthropologist, who at the turn of the 20th century was considered the world authority on the Quechua language, undertook a careful examination of the the von Tschudi and Markham texts. Guided by a desire to clear up the debate, he compared them to other 16th century documents and Quechua texts.

“He concluded that while the story of Ollantay was surely authentic,” Karnis wrote, “the Quechua text had been too Hispanicized to permit the piece as a whole to stand as an ‘indisputably basically indigenous remnant.'”

In 1939, the National Comedy Theatre (Teatro Cervantes), in Buenos Aires, Argentina, adapted the play. The production marked a new chapter in Latin American theater. The play was a colossal hit, running for more than 100 shows, breaking records for consecutive performances.

The Drama-Legend of Ollantay

The Myths of Mexico & Peru, Lewis Spence (1913)

Among the dramatic works with which the ancient Incas were credited is that of Apu-Ollanta, which may recount the veritable story of a chieftain after whom the great stronghold was named.

It was probably divided into scenes and supplied with stage directions at a later period, but the dialogue and songs are truly aboriginal.

The period is that of the reign of the Inca Yupanqui Pachacutic, one of the most celebrated of the Peruvian monarchs. The central figure of the drama is a chieftain named Ollanta, who conceived a violent passion for a daughter of the Inca named Cusi Coyllur (Joyful Star). This passion was deemed unlawful, as no mere subject who was not of the blood-royal might aspire to the hand of a daughter of the Inca.

As the play opens we overhear a dialogue between Ollanta and his man-servant Piqui-Chaqui (Flea-footed), who supplies what modern stage-managers would designate the “comic relief.” They are talking of Ollanta’s love for the princess, when they are confronted by the high-priest of the Sun, who tries to dissuade the rash chieftain from the dangerous course he is taking by means of a miracle.

In the next scene Cusi Coyllur is seen in company with her mother, sorrowing over the absence of her lover. A harvest song is here followed by a love ditty of undoubtedly ancient origin. The third scene represents Ollanta’s interview with the Inca in which he pleads his suit and is slighted by the scornful monarch. Ollanta defies the king in a resounding speech, with which the first act concludes. In the first scene of the second act we are informed that the disappointed chieftain has raised the standard of rebellion, and the second scene is taken up with the military preparations consequent upon the announcement of a general rising. In the third scene Rumiñahui (Stone Eye), as general of the royal forces admits defeat by the rebels.

The Love Story of Cusi Coyllur

Cusi Coyllur gives birth to a daughter, and is imprisoned in the darksome Convent of Virgins. Her child, Yma Sumac (How Beautiful), is brought up in the same building, but is ignorant of the near presence of her mother. The little girl tells her guardian of groans and lamentations which she has heard in the convent garden, and of the tumultuous emotions with which these sad sounds fill her heart. The Inca Pachacutic’s death is announced, and the accession of his son, Yupanqui. Rebellion breaks out once more, and the suppression of the malcontents is again entrusted to Rumiñahui. That leader, having tasted defeat already, resorts to cunning. He conceals his men in a valley close by, and presents himself covered with blood before Ollanta, who is at the head of the rebels. He states that he has been barbarously used by the royal troops, and that he desires to join the rebels. He takes part with Ollanta and his men in a drunken frolic, in which he incites them to drink heavily, and when they are overcome with liquor he brings up his troops and makes them prisoners.

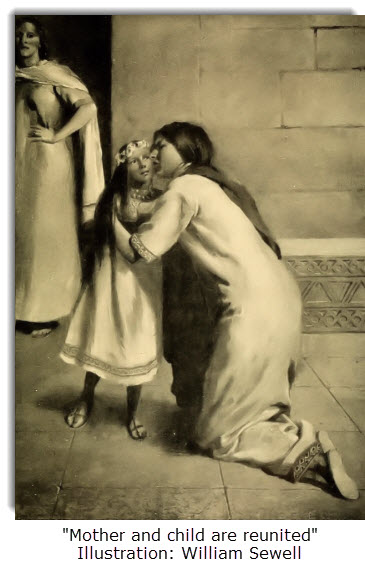

Mother and Child

Yma Sumac, the beautiful little daughter of Cusi Coyllur, requests her guardian, Pitu Salla, so pitifully to be allowed to visit her mother in her dungeon that the woman consents, and mother and child are united. Ollanta is brought as a prisoner before the new Inca, who pardons him. At that juncture Yma Sumac enters hurriedly, and begs the monarch to free her mother, Cusi Coyllur. The Inca proceeds to the prison, restores the princess to her lover, and the drama concludes with the Inca bestowing his blessing upon the pair.

The play was first put into written form in the seventeenth century, has often been printed, and is now recognized as a genuine aboriginal production.

Bibliography:

The myths of Mexico and Peru, Lewis Spence , 1874-1955. U.S. Library of Congress (1948)

Michael V. Karnis, Educational Theatre Journal, Vol. 4, No. 1 (March, 1952)

Hidden treasures in plain sight in Lima: Manuel Pariachi

Hidden treasures in plain sight in Lima: Manuel Pariachi  Pirates in Peru and the Lima DVD dilemma

Pirates in Peru and the Lima DVD dilemma  Aging in the ageless Moche portrait vessels

Aging in the ageless Moche portrait vessels  ‘Pisco Allegories’ winner at International Gourmand Cookbook Awards in Paris

‘Pisco Allegories’ winner at International Gourmand Cookbook Awards in Paris  The final program for Machu Picchu 100-year anniversary celebration

The final program for Machu Picchu 100-year anniversary celebration  The Cusco School of Painting

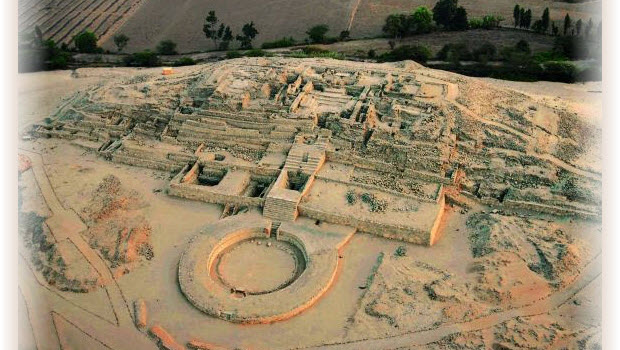

The Cusco School of Painting  Celebrations marking discovery of Ancient site of Caral

Celebrations marking discovery of Ancient site of Caral  Sept. 8 presentation on progress of new Scissor Dance documentary

Sept. 8 presentation on progress of new Scissor Dance documentary

Esse cara tem o mesmo nome que o meu a única diferença e que o meu é olantay que até hoje não sabia o que significava.

É um nome muito bom para ter!