Momentum mounting for stronger laws to protect Peru’s endangered Andean Condor

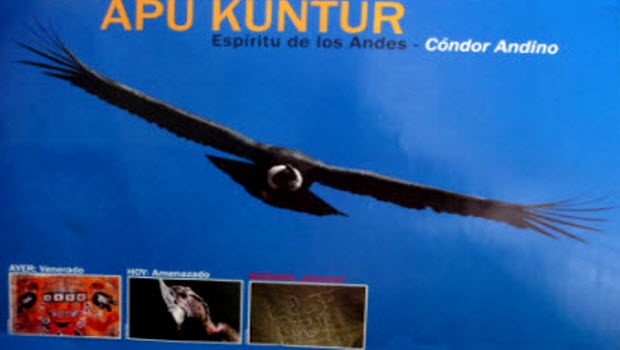

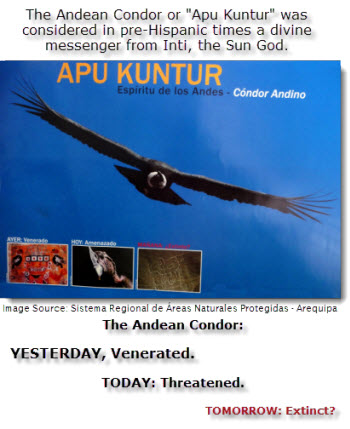

[Originally published January 9, 2013] In pre-Hispanic times, the Andean Condor was known as “Apu Kuntur,” a divine messenger from Inti, the Sun God.

Today, it is an endangered species, illegally captured for festivals, illegally hunted for its feathers and body parts to sell to tourists and use in shamanic rituals, and accidentally poisoned and starved due to human encroachment on its natural habitat.

“Our best estimate, and this is a guesstimate, is that there are 300 to 500 condors in Peru,” Rob Williams, the Peru Country Program Director for Frankfurt Zoological Society, told the Peruvian Times. “They really are disappearing so fast, and this is the slowest reproducing bird of all the birds on the planet.”

A pilot plan to protect the species has been long in coming. Representatives from Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cuzco, the Autonomous Authority of Colca and Annexes (Autocolca), the Andean Condor Working Group and the Frankfurt Zoological Society have been working together for definitive action.

A report published in 2011 by Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Andean Condor Working Group notes:

“The Andean Condor is legally protected in Peru by Articles 308 and 309 of the Penal Code and Supreme Decree

034-2004. These laws prohibit hunting, capturing, possessing, transporting or trading in the species or its body parts and stipulate that such actions are theoretically punishable by up to four years in prison or up to a year community service.”

But the knowledge of the report’s authors, no one in Peru has been prosecuted — ever.

Some of the fatal pressure that the condor faces is not intentional. A widespread practice by Andean farmers of poising feral dogs, foxes and pumas to protect their livestock takes an unknown toll on the birds, which die from feeding on the contaminated carrion.

I am still trying to get my hands on a copy of the proposed legislation now in the works. Local officials are quoted as saying it stresses education and enforcement, and would seek to increase the penalty to a mandatory five-year prison term.

But implementing such legislation won’t be easy, especially if it is perceived as contravening the rights of indigenous communities to maintain their cultural identity — rights enshrined in Peru’s Constitution.

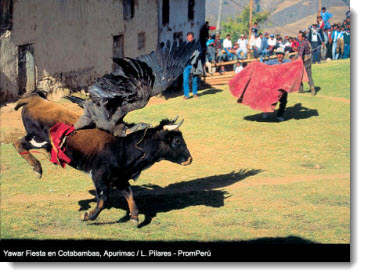

It is hard to predict how such a law would impact the legal status of the Shaman practicing ancient religious ceremonies. Or Peru’s iconic Yawar Fiesta (“celebration of blood” in the ancient Inca language, Quechua). This three-day ritual festival of music and dance is held annually at the end of July in 55 southern Andean communities.

Williams said that female condors are caught for Yawar festivals much more frequently than males. That could be a partial explanation for recent studies showing an alarming imbalance in the sex ratio between adult male and female condors.

There are disproportionately fewer females in a species that does not reach sexual maturity until they are seven, Williams said.

Normally they don’t breed immediately, so probably the first time they try to reproduce is when they are eight or nine, and then ensuing breeding attempts are made every three to seven years.

“So best-case scenario, they breed every three years,” he said. “Worst case, it has been shown that some pairs breed only every seventh year and they raise one chick, if they’re lucky, and those chicks have a 45 percent natural survival rate to adulthood.”

But even that survival rate is an optimistic, outdated estimate.

“This is data taken during the 1970s, when there was still lots more food around, there weren’t people poisoning them, and things as such, in the way they are now,” Williams said. “This is a thing that takes a long time to turn around.”

Williams said he met in November with representatives from Autocolca, the government authority that administers the Colca Canyon.

“They know from their data that the number of condors is declining fast,” he said. “About four years ago, they were seeing an average of 50-plus a day. Now they’re seeing 20-something a day.”

If you like this post, please remember to share on Facebook, Twitter or Google+

Limited train service to Machu Picchu set to resume today, but expect some wrinkles…

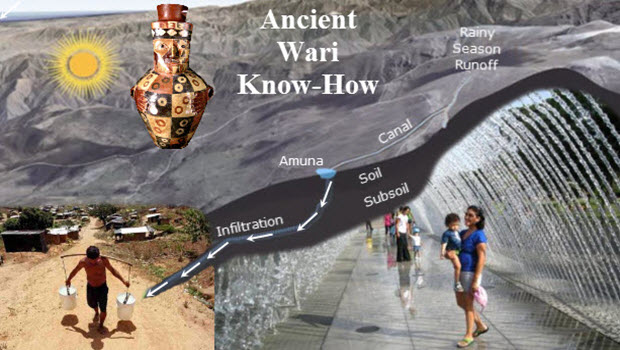

Limited train service to Machu Picchu set to resume today, but expect some wrinkles…  Refurbishing pre-Inca water channels to fix Lima’s desert water woes

Refurbishing pre-Inca water channels to fix Lima’s desert water woes  New Abancay airport will offer easy access to Choquequirao

New Abancay airport will offer easy access to Choquequirao  Timetable for road access to Piscacucho train stop for Machu Picchu-bound travelers

Timetable for road access to Piscacucho train stop for Machu Picchu-bound travelers  Ollantaytambo Residents Shut Ruins to Protest Strict Zoning

Ollantaytambo Residents Shut Ruins to Protest Strict Zoning  UK TV host roasted at home for eating traditional guinea pig dish while on vacation in Peru

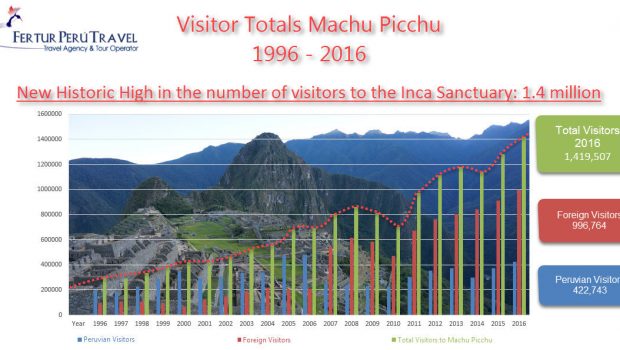

UK TV host roasted at home for eating traditional guinea pig dish while on vacation in Peru  Machu Picchu visitor entry in two shifts will begin in July

Machu Picchu visitor entry in two shifts will begin in July  Inca Rail merger with Andean Railways to broaden train options to Machu Picchu

Inca Rail merger with Andean Railways to broaden train options to Machu Picchu

It is appallig this practise is taking place and that peruvians are the ones perpetuating both the animal abuse and the memory of the conquest. You need to make a petition against the abuse that the international community can sign, condors are humanities biological heritage and the more international attention this issue generates, the bigger the pressure on local authorities to ban and sanction the abuse since it will cause outrage and affect tourism on which many locals are dependent. The petition so far available asks for a DNI which I believe is local ID, not international. Other than this, we can as an international community only share the information with press and tv for the moment. Kind Regards