Hindsight in Cuzco – Nostalgia for the Enchanted City

In the Oscar-winning film “Midnight in Paris,” the main character, Gil, escapes to Paris in the 1920s on a nostalgic journey of self-discovery.

Spoiler alert: After schmoozing with the likes of Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Salvador Dalí, Gil realizes that what’s really ailing him is his inability to deal with his unsatisfactory present.

So Gil resolves to live in the here and now, not the past. He parts ways with his shallow fiancée, Inez, and her frightfully materialist parents, and strolls boldly along the Pont Alexandre III into the future with the beautiful Gabrielle, the girl from the flea market.

Two months later, Gil and Gabrielle get married on a whim. They consult TripAdvisor and see that after April in Paris, the top rated honeymoon destination is Cuzco in June.

Then, as if in answer to the Inca emperor, the Inti sun deity blares, the sky opens and a beam of light extends down from the heavens, enveloping Gil and Gabrielle.

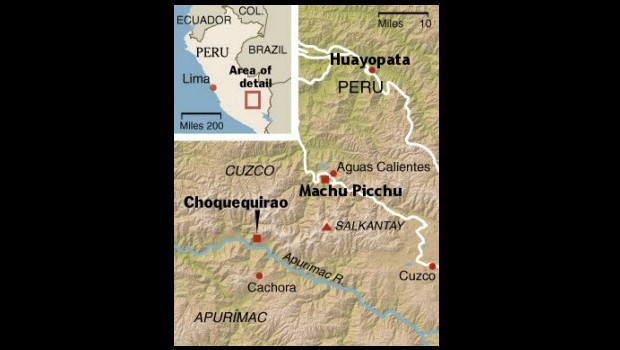

They are transported into a golden age of Cuzco’s past: the 1920s, the intellectual and artistic heyday of Peru’s Indigenismo movement. They are taken in by Albert Giesecke, the Harvard-educated American who 14 years earlier pointed Hiram Bingham in the right direction to “discover” Machu Picchu. They meet Martin Chambi, who takes them to Ollantaytambo and gives them a photography lesson. And they have tea daily with Luis Valcarcel.

The Inca spirit and soul has not merely survived four centuries of crushing repression, Valcarcel tells them, but will grow and thrive in living indigenous culture.

As it happens, Inez also was at the Inti Raymi festival, obsessively stalking Gil and Gabrielle.

She, too, was enveloped by the light and transported, but for her, to an irretrievable Inca past. There, unable to speak Quechua, she makes a tragically comic attempt to talk her way out of being ritually sacrificed.

Meanwhile, four hundred years in the future, Gil and Gabrielle have made Cuzco their home for four months. It is October 1925. They are strolling around Cuzco’s main plaza when they meet and strike up a conversation with a dashing young intellectual, José Graclán.

Graclán is an avid adherent of José Carlos Mariátegui. He tells Gil and Gabrielle that he has just published a short story in the Marxist-leaning magazine Kosko. The tale’s protagonist is a young boy with a troubled soul who wanders the ancient streets of a city held captive by its own walls and the mountains that surround it.

“The city was enchanted; there everything converted into the past,” José says, recounting the story. “Surrounded everywhere by insurmountable walls, the door that led to the future was always closed.”

As José continues, Gabrielle is mesmerized. Gil begins to feel anxious and insecure.

The boy desperately wants to escape into the future, José goes on, but ancient sentries threaten him with an eternal curse. If he leaves, he will never be able to return. One day, however, the boy discovers a secret path to the future and escapes as the guards sleep. He takes with him a cane made from the “tree of the race” planted by his grandparents and a backpack full of memories.

Later, the boy returns to the “tragic city, riding on a cloud” and in so doing breaks the eternal curse. He spurns requests to descend and become the guardian of the path to the future and instead takes his place among the Apu deities.

City elders decree that whoever leaves the enchanted city will someday return in triumph. And so, from that day forward, every new generation would live with their “souls turned toward the future, scrutinizing the future, in search of paths that lead toward glory.”*

That night, Gil tells Gabrielle he is ready to return to their rightful time and place in the future, but she replies that she finds herself irresistibly attracted to José and does not wish to leave.

Gil is shattered. He wanders the ancient empty streets of the Inca capital city until he can walk no more. Resting in a small plaza in the artisan quarter, he notices a strange light emanating from a fountain. He approaches cautiously. The water in the fountain basin is swirling in concentric circles, and in its reflection he sees it, the secret path to the future. He plunges into the pool, and emerges back in his own times.

Upon his return to California, he begins intensive therapy.

John Tierney’s recent piece in the New York Times “What Is Nostalgia Good For?” explains that personal longing for another time and place is no longer regarded as a disease — as it was between the 17th and early 20th centuries.

Nostalgia was originally considered a mental disorder. First coined in the 17th century, it referred to a “neurological disease of essentially demonic cause” found in soldiers suffering a painful longing to return home. Later, it was diagnosed as “meloncholia” or a mentally repressive compulsive disorder, a psychosis of immigrants yearning for their families and cultures.

But contrary to those earlier interpretations, Tierney’s story posits that in measured doses, say two or three times a week, nostalgizing is actually beneficial to counteract boredom, loneliness and anxiety.

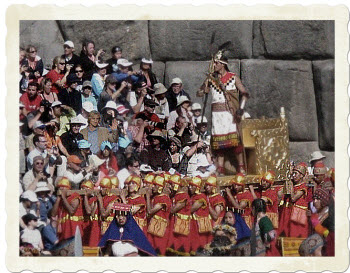

The Festival of the Sun, or Inti Raymi, theatrically recreated in Cusco since 1944, was conceived as a vindication of indigenous identity, as well as a tourism draw. Sketchy, often conflicting, chronicle accounts mention a religious ceremony of the Inca Empire, which took part annually on the winter solstice in honor of the sun God Inti.

To some, Inti Raymi represents the epitome of a ritualized rejection of the present for an imagined, idealized past — or a societal nostalgia.

Further Reading:

Flying ‘Cholo’: Incas, airplanes, and the construction of Andean modernity in 1920s Cuzco, Peru by Willie Hiatt

* The cited excerpts of José Graclán’s story did appear in Kosko magazine and were translated by Dr. Hiatt.

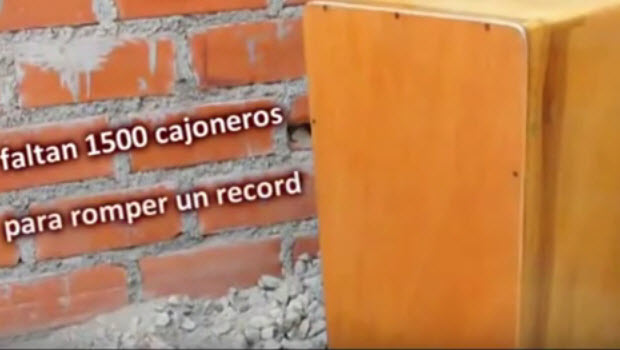

Want to be part in the largest Afro-Peruano Cajón jam session ever?

Want to be part in the largest Afro-Peruano Cajón jam session ever?  UNESCO eyes Q’eswachaka Inca rope bridge for heritage list

UNESCO eyes Q’eswachaka Inca rope bridge for heritage list  The Cusco School of Painting

The Cusco School of Painting  UPDATE: Hiram Bingham road access to Machu Picchu

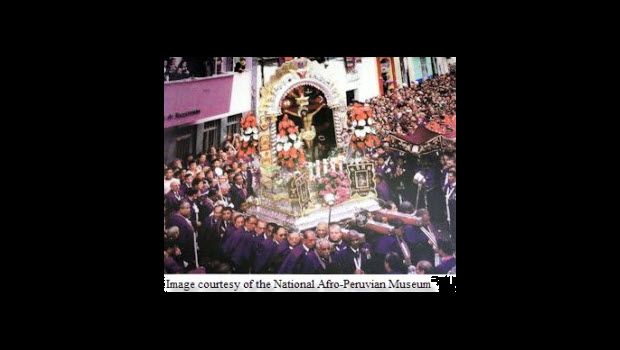

UPDATE: Hiram Bingham road access to Machu Picchu  Lord of Miracles on the job this morning!

Lord of Miracles on the job this morning!  Book your July-August Machu Picchu – Huayna Picchu Holiday

Book your July-August Machu Picchu – Huayna Picchu Holiday  How Thanksgiving Day is Celebrated in Peru

How Thanksgiving Day is Celebrated in Peru  Possible alternative Inca Trail to Machu Picchu reportedly discovered

Possible alternative Inca Trail to Machu Picchu reportedly discovered