Weather Channel could learn something from the Inca and their descendants

When it came to predicting rain months ahead of the harvest, did the Inca’s foresight extend more than 400 light years to the star cluster Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, as part of a cosmic system of weather forecasting?

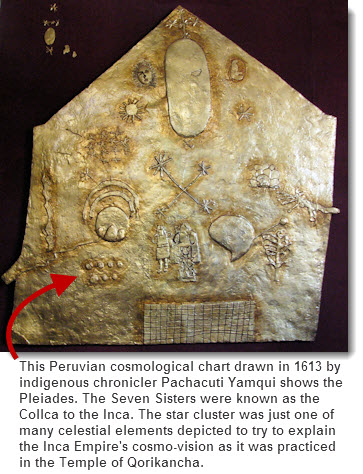

Disappearing from sight in the southern hemisphere around the end of April, not to return until mid-June around the solstice, Pleiades was scrupulously observed by astronomer-priests in the Temple of Qorikancha in Cusco.

The heliacal rising was considered vital for planning the coming year’s harvest and to predict crop yields.

The practice has continued through the centuries. Across the southern Andes in late June, during the longest, coldest nights of the year, peasant farmers climb the high mountain ridges to dizzying heights and peer out, low into the northeast horizon.

As dawn approaches, they’re looking for Pleiades.

According to their ancient beliefs, if the star cluster reappears large and bright, it portends a year of abundant rain and a plentiful harvest.

If, however, the Seven Sisters reappear small and dimmed in a celestial haze, that indicates the rains will be sparse and arrive late. The farmers then know to postpone planting by several weeks.

Viewing the heavens in June to predict rainfall months later couldn’t be anything more than quaint superstition, right?

As it turns out, no. The Inca and their descendants were on to something.

In a fascinating cross-disciplinary study published in 2002 in the journal American Scientist, Benjamin Orlove, John C. H. Chiang and Mark A. Cane posed the question:

“How could the appearance of stars possibly be connected to rainfall? And how, indeed, could people even remember the appearance of stars from one year to the next? Their belief, and the agricultural practices connected to it, seemed as implausible as foretelling the outcome of a battle by examining the intestines of a sacrificed bull.”

What they discovered was a linkage between the oceanic and atmospheric phenomenon known as El Niño and a tropical cloud formation called high cirrus, which is usually so wispy-thin that it’s not visible to the naked eye.

During normal years, this cloud cover does little to obscure the night sky. But the Pleiades star cluster appears hazier from the farmer’s high mountain perch during an El Niño year. That’s because increased moister from the warmer Pacific Ocean carries into the upper atmosphere to feed the cirrus clouds.

Most remarkably, their assessment of the accuracy of this ancient weather forecasting system was around 65 percent.

“This exceeds the accuracy of modern scientific forecasts with similar lead times for precipitation over the Andean highlands, which ranges from 55 to 60 percent.”

If you like this post, please remember to share on Facebook, Twitter or Google+

Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum

Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum  Blitzing the Incas

Blitzing the Incas  Machu Picchu is the climax after the Lares Valley Trek

Machu Picchu is the climax after the Lares Valley Trek  Visit us in our new office in Cusco!

Visit us in our new office in Cusco!  The spiritual afterlife of dogs in Peru

The spiritual afterlife of dogs in Peru  President García: Yale will return entire Machu Picchu collection

President García: Yale will return entire Machu Picchu collection  New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu

New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu  The romantic journey to Machu Picchu

The romantic journey to Machu Picchu

The Incas, the amazing culture!!!!! Irá have been todo Cusco.