This Week Magazine: Inca Gold

Remember Polly Ann Meredith, ace girl pilot for G-BAT? Now she and her gang are in South America on Good Neighbor business… and in quick trouble too… In this exciting first story of a new series.

By Hoffman Birney

Illustrated by Courtney Allen

A Short Story Complete in This Issue

(Originally published in The Milwaukee Journal, July 28, 1940)

“You’re right, it is,” said Jim Vancamp, “but G-BAT doesn’t get its grant to operate air-freight lines in Peru until it puts up that much as a guarantee of good faith. These South American countries have been left holding the bag before with wildcat development schemes that never got beyond the stock-selling stage, so you can’t blame Peru.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Who’ll be at the dinner tonight?” asked Joan Vancamp, wife of the head of the G-BAT mission – short for Great Basin Air Transport.

“A lot of the government higher-uppers,” said Jim. “You’ll also meet a bird named von Kleinschmidt. He’ll have an ear wide open for any chance significant remarks our crowd may make, so your cue and Polly’s is to be beautiful and very dumb. Not a word about the situation here or the concessions we’ve gotten in other countries.”

“What’s von Kleinschmidt’s place in the picture?” asked Polly, who was G-BAT’s only woman commercial pilot.

“Wish I knew,” said Jim, “but his finger is somewhere in the pie, and it’s a cinch he’s not working for us. It’s my guess that he’s interested in seeing a foreign airline get the franchise were working for, and that he was the one who inspired somebody here with the idea of demanding that big guarantee.

“Getting the money will delay us, of course, and any delay will help another outfit that isn’t as ready as we are to talk business.”

He bowed over Joan’s hand, then raised his eyes to hers. They were blue eyes, flecked with tawny spots like the eyes of some cats, and deceptively placid. The eyes of one who had known intolerable disciplines or who had witnessed unspeakable cruelties and could gaze unmoved upon more.

Joan Vancamp felt in him the sudden impact of a menace more terrifying because it was undefinable. She was suddenly glad that the men at that dinner outnumbered the women by three to one, glad when she saw von Kleinschmidt seated far down the long table next to John Curtiss, the Bolivian-born interpreter of the G-BAT mission, and she turned quite gaily to her own dinner companion, Dr. Hippolyte Maldonado.

Jim’s warning was in her mind, and she steered the conversation to such safe subjects as the magnificent scenery of the Andes, the ancient Inca ruins of Cuzco which she and Polly Meredith had visited, and the Quechua Indians as she had observed them in the mountain hamlet of Tacimu.

“I have heard of your stay in Tacimu, Mrs. Vancamp,” Maldonado observed – like all educated Peruvians he spoke faultless English – “and it is quite modest of you to refer to it as a visit. You and Ms. Meredith deserve great credit. Very few people would have been so brave as to nurse an Indian child through smallpox.”

“Don’t call it bravery, please. We were both of us petrified with fear. Polly recognized the disease – she’s a registered nurse, you know – but I really think we’d have run away except for the child’s father. His eyes looked like a hurt dog’s and we just couldn’t leave that little boy to die. Polly deserves the credit for pulling him through – all I did was help her a little and interpret for her.”

“Ah – you speak Spanish?”

“Not your kind – just the kitchen-Spanish that I learned as a child in New Mexico. I can make people understand me and I know most of what they’re trying to say – and that reminds me of something, Doctor. The word joven means ‘boy,’ doesn’t it?”

“Yes. More exactly, perhaps, a very young man, a youth.”

“That’s what I thought, and I couldn’t understand why the sick boy’s father applied it to himself. His name was Indelacio Almagro, and he always added ‘Almagro el Joven’ – ”

“He did!” the Peruvian started. “But, Mrs. Vancamp, that is astonishing. You are not familiar with our history, then?”

“Not at all – except that Peru was conquered in fiftheen-something by Francisco Pizarro, whose bones can be seen in the Cathedral here in Lima.”

“Diego de Almagro was one of his officers, but he quarreled with Pizarro and was executed. He left a half-caste son, Almagro el Joven, whose followers fomented the conspiracy which resulted in Pizarro’s assassination. They tried to make El Joven ruler of Peru but they were defeated and The Lad as he is called, was captured and beheaded in the Plaza at Cuzco in September of 1542. And now you tell me of a Quechua Indian who proudly claims the same name!”

“I think she must have been entitled to it,” said Joan, “because when we left he gave us the use silver cross which he said had been in his family ever since the first Almagro. We didn’t want to take it – you know how terribly poor those Indians are – but he insisted. Would you like to see it?”

Most decidedly. Dr. Maldonado would like to see that cross. He reminded her of her promise as soon as the group that adjourned to the sala for coffee. Joan new afterwards that it was a mistake to bring the relic to the crowded room, for the entire party clustered around Maldonado’s chair as he called attention to the intertwined initials “Do. de A.” at the intersection of the arms.

“Diego De Almagro, the father of El Joven. This is unquestionably authentic, Mrs. Vancamp. By the way, is it empty?”

“Empty?” It was Polly Meredith who echoed the word.

“Yes. See the tiny hinges and a broken stub of the catch? Many crosses, modern as well as antique, are made in that way. The interior space serves as a reliquary for some sacred object.”

“I never thought of it.” Joan confessed. “Will it open, Doctor?”

“I think so.” He fumbled in his pocket, but it was von Kleinschmidt who produced the penknife. Maldonado inserted the thinnest blade in a broken catch. It yielded, and at a slight lateral pressure the entire rear of the cross opened to reveal a cavity which held a tightly rolled parchment. Tiny flakes crumbled from it as von Kleinschmidt stabbed at it with an eager forefinger.

“Open it, Doctor,” he demanded. “It may be…”

“It may be many things.” The historian thrust aside the intruding hand. “But it is four centuries old and it must be unfolded with the greatest possible care. With Mrs. Vancamp’s permission, I will take it to the museum.”

“Certainly,” Joan bowed, then suddenly amended the permission. “It is very late though; I think it would be better to put it in the safe here in the hotel until morning. If you’ll excuse me, I’ll do so right now.”

Later, in their own room and with the cross beneath her pillow, she flames to her husband:

“it was von Kleinschmidt who made me change my mind about putting it in the safe, Jim. He could hardly keep his hands off that paper. Lock the door and proper chair against it. Oh, Jim, darling, I’m actually afraid of that man!”

There were four sheets of parchment in the cross, all covered with script which had faded through the centuries to the color of weak coffee. Three of the four, Maldonado announced after more than a week’s study, formed a letter in the hand of Diego de Almagro to his son. The fourth. “It is not signed, which is a great pity,” said the scientist, “but it was written after the defeat at Chupas. The writer knew of El Joven’s impending execution and was determined that the treasure which had financed the revolt would not fall into the hands of the new governor, Vaca de Castro.”

“Treasure?” Tacks Malone, G-BAT pilot, pounced on the key word.

“Yes — and a very great treasure. I will spare you a complete translation of the very wordy archaic Spanish. Briefly, this document tells where El Joven’s followers hid the golden chain which legend tells us long enough to pass entirely around the Huaca Pata, the holy square in old Cuzco. We know that the square measured approximately 600 feet on a side — twenty-four hundred feet of gold!” He looked up quickly as two of his auditors snickered.

“We — Joan and I — once contributed $1000 toward rediscovering the lost mine in Nevada,” Vancamp explained. “It was — well, it turned out to be very successfully lost.”

“This is Peru, and the most fantastic stories you can imagine won’t even approach the truth of the treasure which is buried here. We know — forgive me if I seem to be lecturing — that the Spaniards strangled Atahualpa, the great Inca ruler, and that the treachery cost them all but a very small portion of the huge ransom that had been raised for his freedom. The balance was hidden. Some say that it was thrown into Lake Titicaca — ”

“Isn’t that the treasure which is called the Big Fish?” Joan Vancamp interrupted. “We were told about it Cuzco, all the legends of buried treasure seem to end there.”

“And why not?” asked Maldonado testily. “Cuzco was the capital of an empire which extended from Ecuador over all of the present Peru and Bolivia and far into Argentina and Chile. All that territory sent tribute to the Inca in the Holy City of the Sun. Gold wasn’t money — it had worth only because it was a beautiful metal and easily worked.

“In the Temple of the Sun — now the monastery of San Dominic and Cuzco — there was a golden disc more than six feet in diameter and three inches thick. The Incas laid golden pipes deep in the ground to carry water to fountains with golden spouts, and they created the Garden of the Sun, with stems, leaves, and flowers made entirely of gold. All that and a thousand other stories are historical, so don’t scoff at any story of buried treasure in Peru, or at the idea of a golden chain nearly half a mile long.”

“But do you think the parchment is genuine?” Polly was breathless.

“Unquestionably! I have studied too many ancient documents to be hoaxed. It was written by one of El Joven’s captains who personally supervised the burial of the golden chain. He gives landmarks which should have changed very little even in four hundred years, and locates quite accurately the Temple, old even in 1542, in which the gold was hidden. I won’t make any predictions as to whether or not the gold still there. The Conquistadores had no equals as looters of hidden treasure.”

Tacks Malone laid down his pencil, whispered to Lance Riker, the G-BAT communications expert, then spoke to his chief. “D’you know, boss,” he said, “that with gold at thirty-five an ounce, and allowing that the chain would run at least a pound to the foot, it adds up to pretty near a million and a half!”

“There were twenty million, we were told, in the lost mine we sunk our money in,” said Vancamp, shaking his head. “Stick to poker,Tacks, it’s less of a gamble.”

Joan nodded accord and Malone turned to Polly Meredith. “Speak up, Polly. That cross was given to the two of you.”

“I don’t know what to say. It’s more money than I can even think about.”

“Doctor, suppose we should find a treasure, what’s in it for us?” said Tacks.

“Seventy-five percent of the gross,” the scientist replied without hesitation. “Peru has very definite laws on the subject. You file a denuncio which describes the treasure and its location so far as known, and commits you to deliver to the governments twenty-five percent.”

“Which would still leave plenty.” Tacks faced his companions. “Listen, gang, there are six of us altogether, you two Vancamps, Polly, Lance Riker, John Curtiss, and my good self. We’ll all be old some day, and it’d be nice to salt away now enough to retire to some island paradise. The time to gamble was now. Count out the two girls, because they were the ones who got the cross. I’m willing to put up my quarter-share toward the pot, if any, to be split six ways. There is the proposition — make your bets while the little ball rolls!”

We flew from Lima to Cuzco, then established a camp in the same valley through which the followers of El Joven had fled.

Their search for the treasure was like that of a chemist who experiments endlessly and tirelessly with compounds of a single drug. They first searched for “a spring in the shadow of a great rock” and eventually found it by tracing to their buried sources the waters of the marshy pool where the llamas and cattle drank.

Then they went “a league to the northward,” — with full knowledge that the league of the ancient chroniclers varied greatly, and that wearied men, harried by pursuit and burdened with the weight of treasure, were poor judges of distance.

“There were raised three mounds to a height of three estados above the ground and in the small temple of great rocks we buried the chain…” At that point the parchment had been creased and several lines were wholly illegible.

There were many mounds in the valley, and the search became a probing of one after another with steel rods.

One day, after the searchers had explored one of these mounds and found only three huge cut stones, the Quechua labor foreman came to Maldonado. He pointed to one of the Indian workers. “That one says, Señor, that there is another wall beyond the stream. A part shows above the ground.” A foot of wall face was exposed where the man had uprooted a tola bush for fuel. A few minutes’ work revealed a second huge block, so shrewdly fitted to the first that a knife blade could not be forced into the crack between.

While this new discovery was being feverishly followed up, no one noticed that a strange Indian had joined them until he stood almost beside them and spoke in the Quechua tongue to the nearest worker.

The man looked up, stopped working, and then hurriedly nudged another Indian, who passed the word along until all the laborers had laid down their tools. Even the Quechua foreman disregarded Maldonado’s angry order enjoined his fellows. Not until then did the newcomer — ignoring orders to halt — descend the bank and examine the excavated walls. A coal-black llama kept close at his heels.

The newcomer wore a wide Quechua hat, with upturned brim. A graceful, beautifully woven poncho, new and clean, fell from his shoulders almost to the ground. His face was a deeply chiseled mahogany mask, inscrutable. He walked slowly along the wall, then laid his fingers on a dirt-clogged carving and spoke briefly in the Quechua language. None of the Indians replied.

The stranger placed his hand on the llama neck and with his forefinger made the gesture of drawing a knife across its throat.

“Dios mio!” Maldonado exclaimed, “the sacrifice of the black llama!”

But his whisper was drowned in the flood of protest from the Quechuas.

The man dropped his hand and turned away, the llama treading behind him.

“What’s the idea?” demanded Tack Malone.

“Magic of some sort, of course.” Maldonado’s eyes followed the retreating figure. “There were ancient Incaic rights in which a black llama was sacrificed.”

“Look at your workers,” exclaimed Lance Riker. “They’re doing a walk-away strike.”

The Quechuas were marching toward their camp. There they packed their llamas and burros and departed, driving the beasts before them. Maldonado raved, but his threats to withhold all pay until work was resumed detained only the foreman who, after long questioning, explained the incident.

The stranger, he said, was a medicine priest, whose fame extended over all the province. He had told them that further work on the buried temple where the old gods slept would result in their wives becoming barren, their crops failing and for the rest of their days, peace neither in this world nor beyond the grave.

This is von Kleinschmidt’s work, I’ll bet,” said Vancamp.

“Which means,” said the scientist, “that we’ll get no more workers. All of the Indians for miles around will know of this before sunset. The witch doctors’ power among the Indians of Peru and Bolivia is greater than that of church and state combined.”

“So endeth that chapter.” observed Tacks Malone. “Say, Doctor, do you still think that gold is under this dirt?”

“I don’t know, and if it wasn’t for you people, I’d say I didn’t care. This building is treasure enough for me — a pre-Incaic structure which has escaped both the Inca’s rebuilding and the looting of the Spaniards. I’m going to excavate it if I have to carry every kilo of earth away in my hands!”

“Stout fella! What do you say, G-Batters, shall we join up with the doc? He can have the little brown church in the dell — all we’ll take will be the million bucks in gold!”

The weeks that followed were a nightmare of toil. A few Spanish laborers were recruited in Cuzco, but it was the pick-and-shovel work of the four Americans which slowly uncovered a building nearly thirty feet square, with a single opening which faced the east.

Within the monolithic wall was a slab roofed shrine which once had contained a statue of Viracocha, the creator God who was worshiped by the mountain people long before the advent of the Incas. But the followers of Almagro el Joven had torn with God on another day from his pedestal and cast him face down in the courtyard of his own temple. In his place was an Incaic burial pack — huge bundle of many wrappings of woven fabrics within which, tightly flexed in prenatal attitude, was a human body. There was no sign of the golden chain of Huaca Pata.

“Too light —” Lance Riker threw his long arms around the funerary bundle and heaved — “there’s no gold sewed up in here.”

“Don’t move it!” Maldonado ordered sharply. “Someone’s coming — on horseback. Let everyone be on his guard.

It was von Kleinschmidt. He dismounted, glanced from one to another of the dirt-grimed, weary Americans, then peered into the dark shrine. “So!” he exclaimed, “the chain is not here.”

Vancamp gripped his elbow and spun him around. In the G-BAT leader’s voice was all the venom engendered by weeks of back-breaking labor which had ended in disappointment. “You know too much,” he snarled. “We’re not in Lima now and I’m talking plain, von Kleinschmidt. Get out before your throne out.”

“Let him stay,” Maldonado interjected. “He has been so interested in this affair, even to the point, evidently, of bribing museum attendants to find out where we were. Lance, my friend, will you and Curtiss lift down that burial pack?”

The two raised the great bundle from where it had rested for four centuries. Beneath was the circular opening of a stone-lined crypt in which, link piled on dull-gleaming link, was a mound of dusty chain — the golden chain which once had barred the commoners of Cuzco from admission to the Holy Square!

John Curtiss, the nerveless, was the first to move. He told on the nearest link and dragged from the crypt the first of the twenty-foot lengths into which the chain had been cut to facilitate handling. Then another, and another, until the shrine was empty and thirteen of the lengths lay on the ground. As each appeared, Malone measured it.

“Just two hundred and sixty-five feet.” he announced. “I thought you said that square measured twenty-four hundred, Doctor? Something’s shrunk.”

No more was found, either then or in the later excavation of the building. Either the balance had been hidden in another place or, as was nmore probable, had been sold link by link to finance the Almagro revolt.

“Scarcely up to expectations, is it Mr. Malone?” Von Kleinschmidt laughed unpleasantly. “About ten percent of the millions you…”

He turned as the hoof beats drummed from the hard-packed soil. A man in the uniform of an officer of the Civil Guard, the national police force of Peru, dismounted at the excavation and inquired in Spanish for Señor Vancamp.

“A telegram,” he explains. “It was received yesterday and was referred to my captain, who ordered me to bring it here without delay.”

Vancamp tore open the envelope and read the few words of the message, then stepped quickly toward the German: “is this another sample of your dirty work — you’re delaying tactics?” he snapped. “By heaven, von Kleinschmidt, I…”

Lance Riker stepped between the two as he read the danger signs in Vancamp’s doubled fist and the pulse that throbbed visibly at his temple.

“What is it, chief?”

“What’s the date today, Lance?” Vancamp seemed to stare through his subordinate. “The fifteenth? — I thought so — It means we’re licked, that’s all. While we’ve been up here hunting treasure, back in Lima they’ve cracked down on us. Secretary Forga is away, and someone in his office has succeeded in having the government’s agreement with us amended to say that that hundred thousand must be deposited by noon tomorrow or our franchise will be canceled. Of course the deposit hasn’t come through from the States, and won’t in time. Tomorrow noon! I couldn’t even get a telegram through to Lima, let alone the States by that time.”

The blood surged to his face, then receded as suddenly. “Lance,” he said quietly, “if you’ll step out of the way, I think I’ll kill that double-dealing von Kleinschmidt!”

The German retreated half a pace and a flat automatic pistol materialized suddenly in his hand. Tragedy stood unveiled in the ancient temple until Tacks Malone spoke.

“Keep your shirt on, boss. There’s the hundred thousand you need, right there on the ground. We’ll load it on the transport tonight, take off at dawn, and we’ll be in Lima before the government is even out of bed.”

“You mean… all of you…” Vancamp stammered.

“Why not?” The other funds will be coming along soon enough, and in the meantime we’ll just loan G-BAT what she needs to go ahead with the job we came down here to do. Me, I won’t even charge the line interest… just seeing the look on von Snugnose’s face is pay enough for me. We’ll take the apple and he can have the worm. Come on — heave ho, my hearties.”

~The end~

Source: Google News Archives

Hidden Inca treasure in the old headlines

Hidden Inca treasure in the old headlines  Why did Peru’s most famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa punch his best friend Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the face?

Why did Peru’s most famous writer Mario Vargas Llosa punch his best friend Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the face?  Strange Story From Peru: The dictator’s mistress and the reluctant bridegroom

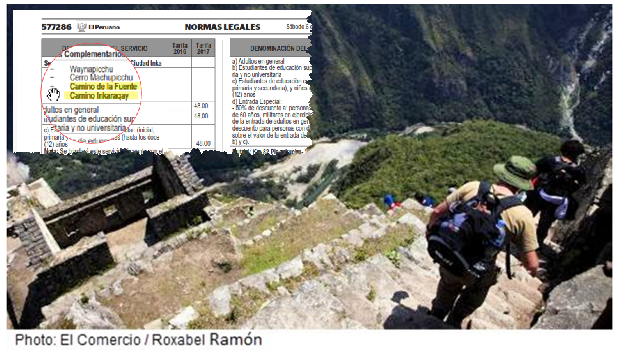

Strange Story From Peru: The dictator’s mistress and the reluctant bridegroom  New Machu Picchu Treks – Adenalin-packed and Contemplative

New Machu Picchu Treks – Adenalin-packed and Contemplative  The Cusco School of Painting

The Cusco School of Painting  Inca Trail to Machu Picchu as Covid-19 wanes

Inca Trail to Machu Picchu as Covid-19 wanes  Andean conceptions of the afterlife

Andean conceptions of the afterlife  As close to heaven as it gets for train enthusiasts for 2013

As close to heaven as it gets for train enthusiasts for 2013