Machu Picchu before and after…

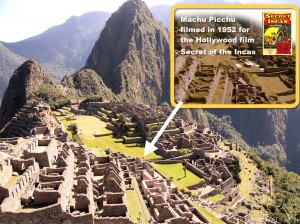

For an interesting perspective into how much restoration has taken place at Machu Picchu, independent American researcher and explorer Paolo Greer suggests watching a B-movie classic, Secret of the Incas.

The 1954 Paramount Pictures movie, starring Charlton Heston, was filmed on location in Cusco and offers a brief, but stunning, panorama of Machu Picchu.

That shot, when compared to the Inca Citadel today, reveals that many of the now-pristine outlying buildings in the Western Urban Sector were in fact collapsed piles of stone.

An argument can be made that the representative features of the restored architectural units remain true to the larger site and convey its significance.

But not everyone agrees. To quote author Peter Frost, from his book, Exploring Cusco:

“It is said that when the anthropologists arrive, the gods depart. In my opinion, something similar happens with reconstructors of archaeological sites. Imagination is crushed; the mystery, the allure and the enchantment depart. (Many archaeologists would add: and with them goes a lot of irreplaceable information; for these are sites that can no longer be studied in their particulars.)”

Machu Picchu’s Cinematic Debut

In the 1930s and 40s, Peru’s focus at Machu Picchu was on restoration and preservation.

A small tourist lodge was constructed in 1934 adjacent to the ruins. And in October 1948, the Hiram Bingham highway, a switchback road leading up to Machu Picchu, was inaugurated. (Hiram Bingham himself returned to Machu Picchu for the first time in over 30 years for the ribbon cutting ceremony.)

But Machu Picchu’s status as a world-class tourist destination was still decades away. As Charlton Heston’s character remarks to Nicole Maurey while they pause along the Inca Trail in Secret of the Incas, “There won’t be anyone there, a few Indians maybe … not many people go to Machu Picchu.”

It was only after the release of Secret of the Incas that the real transformation at Machu Picchu started to take shape.

The 1950 Earthquake and Cusco’s Struggle to Rebuild

The government of General Manuel A. Odría, who had seized power in a 1948 coup d’état, moved sluggishly to rebuild Cusco after the devastating earthquake of May 1950. That was the backdrop for Hollywood’s incursion into the sanctuary.

By 1954 — with global audiences captivated by Machu Picchu’s mystical allure as showcased in Secret of the Incas — pressure was mounting to revive Cusco’s moribund tourism industry.

By 1955, that pressure had swelled into a national outcry.

The anticipated flood of visitors clamoring to witness the grandeur they had seen on the silver screen wasn’t materializing. Cusco’s shattered tourism infrastructure was woefully unprepared to accommodate even a modest stream of tourists, let alone the influx Peruvians hoped for.

Making Machu Picchu

Historian Mark Rice tells the definitive story about the citadel’s modern history in his book Making Machu Picchu.

According to Rice, the debate over ‘reconstruction versus preservation’ at Machu Picchu took shape gradually.

A newly formed Corporación de Reconstrucción y Fomento del Cuzco, was tasked by the government in 1955 with a more aggressive approach, signing off on the use “tools of steel, powder, wheelbarrows, and cement.”

This marked a sharp departure from traditional restoration methods that used only original materials and traditional construction techniques.

Debate over Machu Picchu Authenticity

El Comercio, then as now Peru’s most important newspaper, expressed concerns on its editorial pages about the slow pace of preservation efforts. It criticized the use of only three workers at the site, mockingly questioning how the “most captivating fortress in the world” could be treated so negligently.

The newspaper pushed for more aggressive efforts, focusing on preserving Peru’s heritage and meeting the expectations of a still small, but burgeoning tourist population.

José María Arguedas, a renowned sociologist, writer and founder of Peru’s neo-indigenism movement, took a pragmatic view of the use of modern materials in restoration efforts.

“The casual visitor, and even the educated visitor, but perhaps not an expert, will not be able to differentiate the original part of the ruin from the reconstructed,” Arguedas wrote in a news article.

Archaeologist Manuel Chávez Ballón initially supported the modern reconstruction approach, but by 1957, he started to decry how “the interest of the tourist” overshadowed the historic integrity of the sanctuary.

Chávez Ballón also worried about the alarming absence of documentation to record what was being rebuilt as opposed to restored.

Mark Rice recounts how Manuel Chávez Ballón sarcastically remarked that “the archaeologists of the future are not going to be able to explain why the Incas only used lime, cement, and iron at Machu Picchu, and nowhere else.”

D-shaped Wari Temple Discovered in Cusco’s Vilcabamba Jungle

D-shaped Wari Temple Discovered in Cusco’s Vilcabamba Jungle  Alternative Lima Tour: Royal Felipe Fortress

Alternative Lima Tour: Royal Felipe Fortress  Momentum mounting for stronger laws to protect Peru’s endangered Andean Condor

Momentum mounting for stronger laws to protect Peru’s endangered Andean Condor  Extra! Extra! Crowds through the clouds to Choquequirao

Extra! Extra! Crowds through the clouds to Choquequirao  The Story of the Luxurious Belmond Hiram Bingham Train to Machu Picchu

The Story of the Luxurious Belmond Hiram Bingham Train to Machu Picchu  Old Time Radio: Secret of the Incas

Old Time Radio: Secret of the Incas  Uros: Floating Islands in Peru

Uros: Floating Islands in Peru  The virtual reality of Inca architecture: Sacsayhuaman

The virtual reality of Inca architecture: Sacsayhuaman