Lost Huacas: the challenge of reclaiming Lima’s pre-Columbian past

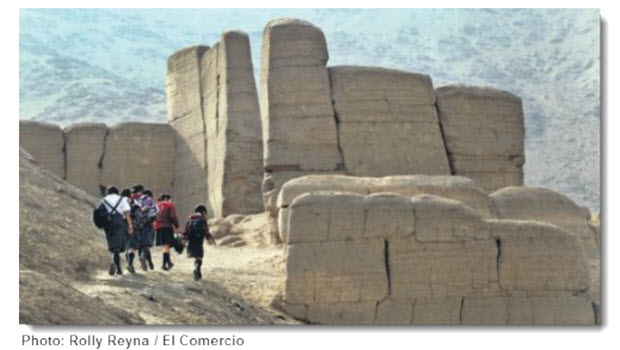

Six school girls in Peru’s capital city passing through a 2,000-year-old archaeological ruins as part of their daily routine. It’s a poignant image and a tribute to how cultural patrimony can appear to integrate seamlessly with daily life.

Click on the photo and you’ll land on an article in Peru’s leading newspaper, El Comercio, about its efforts to raise awareness to preserve Lima’s few remaining pre-Columbian monumental structures.

The article by Javier Lizarzaburu opens with a statistic: Lima has 350 archaeological sites. At first glance that does not seem like a few. It sounds like an enviable abundance of cultural patrimony.

But not if you take into account that in the last 200 years, 60 to 70 percent of Lima’s huacas – ancient temples, forts, cemeteries, administrative centers and their contents – have been flattened, burned and buried.

Some of the worst devastation occurred during the 20th century.

Major burial mounds were knocked down and plowed under to make way for the city zoo, university campuses, and several hospitals. Construction of private estates and major avenues cut directly through dozens of massive pre-colonial ruins. In recent decades, impoverished Andean migrant squatters, seeking a better life in the coastal capital, doused any mummies they found with gasoline and set them ablaze, rather than risk being forced from their makeshift homesteads in the names of science and Intangible Cultural Heritage.

El Comercio’s “nuisance to opportunity” article was preceded a day earlier by an excellent interactive map of Lima’s huacas, along with photos of 60 of the capital’s under-appreciated pre-Inca archaeological sites.

For the most part, Lima’s 350 archaeological ruins are the scant remains of ancient adobe pyramids and walls, which stand out on Lima’s chaotic streets like islands in a churning sea of poorly planned and barely controlled urban development.

Getting a handle on that legacy in a teeming city of nine million inhabitants — even now after more than a decade of booming economic growth — remains a huge challenge. Competing priorities often boil over into political conflict.

An example is the battle between the Ministry of Culture and the Municipality of Ate Vitate over a planned highway extension from Avenida Javier Prado to the Central Highway. The flyover, as planned, would gouge a broad path through the middle of the protected Puruchuco/Huaquerones archaeological complex, potentially destroying priceless relics, as-yet undiscovered. The limited excavations conducted in the protected zone by archaeologists Elena Goycochea and Guillermo Cock have produced the richest treasure trove of mummies and artifacts pinpointing the historical transition from Inca imperial rule to the Spanish Colonial era.

Where major public works projects aren’t a burning issue, some of Lima’s district’s have tried to find economic models to preserve their archaeological sites, satisfying both the needs of science and the local communities.

For the last decade, Lima’s district of Miraflores has leased space to the Huaca Pucllana Restaurant, one of city’s finest gourmet eateries, where patrons dine just meters from the magnificently lit adobe pyramid built by the Lima culture (200-700 AD). A portion of the restaurant’s profits are allocated to restoration and ongoing scientific research at the site.

Most archaeological ruins don’t have the benefit of being located in the posh, tourist-rich environs of Miraflores. For less fortunate communities, the possibility of such a marriage between an archaeological ruins and a five-star restaurant drawing thousands of foreign tourists is a distant dream.

That does not mean, however, that there aren’t riches to be derived from ancient huacas, wherever they are located.

“There are people who live in front of archaeological monuments that are garbage dumps or refuges for low lifes,” Pedro Pablo Alayza, deputy director of cultural affairs for the Municipality of Lima, told El Comercio.

José Félix Huaring is a high school teacher and general coordinator of the Kusillaqta Project, a grass-roots cultural organization that’s been instrumental in reclaiming the Huaca Mangomarca in San Juan de Lurigancho. Just five years ago, the ancient site was a garbage-strewn haven for drug addicts and violent gangs.

The Kusillaqta Project has helped turn the huaca into a valued community asset. “This includes exhibitions,” Félix told El Comercio, “and regular tasks to clean the huaca, with students from various schools and local residents, and with support from the National Institute of Culture and the municipality.”

During the last four years, Mangomarca has been the site of a community festival celebrating the Inca December solstice ceremony with an elaborate re-enactment by actors and dancers, young an old, from the neighborhood.

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival

Book your Cusco trip featuring the Inti Raymi Festival  Is that the Inca Creator God you see in the cliffs overlooking Ollantaytambo?

Is that the Inca Creator God you see in the cliffs overlooking Ollantaytambo?  The Machu Picchu Master Plan 2015-2019

The Machu Picchu Master Plan 2015-2019  Inti Raymi Festival 2022 returns after 2-year hiatus

Inti Raymi Festival 2022 returns after 2-year hiatus  No Suspension of Adventure Sports Tourism in Cusco

No Suspension of Adventure Sports Tourism in Cusco  Llama-supported treks coming soon to Peru’s Chaparrí Reserve

Llama-supported treks coming soon to Peru’s Chaparrí Reserve  Tijeras – The Scissors Dance

Tijeras – The Scissors Dance  New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu

New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu