Vilca Lords and the Lord of Wari on exhibit in Cusco

In case you haven’t heard, there was an astounding archaeological discovery announced last week in the Vilcabamba region of Cusco, an area known historically as the last refuge of the Inca.

The reason for excitement is that this is one of those “missing link” discoveries — the type that gives Peruvian archaeology an unexpected push in a new direction, opening a whole new perspective.

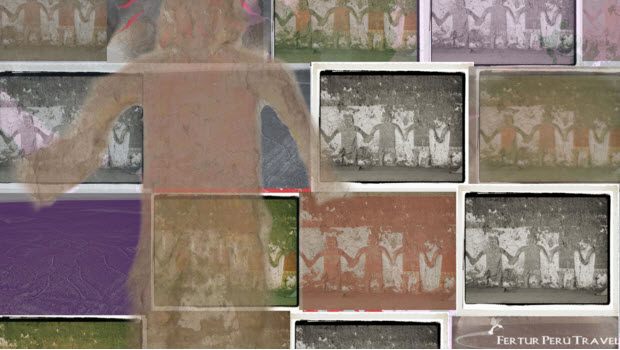

The tombs didn’t belong to the Inca Empire, but instead to the Wari, a culture that flourished between the 6th and 10th centuries AD. They are believed to have ruled a vast territory stretching along the Pacific coast and across the Andes, eventually joining forces with the Tiahuanaco, whose religious and administrative influence was centered around Lake Titicaca.

But vestiges of Wari culture had never been found anywhere near Cusco’s southern Amazon jungle.

Culture Minister Juan Ossio called the Wari discovery remarkable and surprising.

“Once, a Dutch anthropologist, Tom Zuidema, told me that possibly the Inca were subjugated by the Wari and provoked a rebellion,” Ossio told Radioprogramas, “and from that rebellion gained their independence and inherited the cultural patterns of the Wari to develop their own political system.”

A team of government-employed archaeologists, excavating the complex of Espíritu Pampa, unearthed — among other things — a Y-shaped silver chest plate, a silver mask and silver-plated walking stick, and two golden bracelets embossed with anthropomorphic feline figures.

Javier Fonseca, described by Radioprogramas as the leader of the excavation, said the remains found in the citadel appeared to belong to Wari’s theocratic military caste.

Fonseca, 32, said that when he saw the first signs of the main tomb, he could not believe that it was not of Inca origin.

“The first feeling was emotional, but I had to be cautious until I had in my hands the first complete piece,” he recounted. “And I shouted with excitement because I realized that this was something big.”

Peru’s archaeology community agrees. The find has been widely heralded as one of the most significant finds since Walter Alva’s 1987 discovery of the Moche Lord of Sípan, or even Hiram Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu 100 years ago in July.

It was at Espíritu Pampa that Manco, the last of the Royal Inca, fled from the Spanish conquistadors after losing the Great Rebellion of 1536. Establishing a center of resistance known in Quechua as Vilcabamba, or sacred pampa, Manco waged hit-and-run raids for years from the jungle stronghold against his Spanish enemies in Cuzco. His guerrilla war ended in less than a decade with his assassination by seven Spanish fugitives to whom he himself had provided refuge.

Yale history professor Hiram Bingham was on the hunt for Vilcabamba in 1911 when he found Machu Picchu instead. Bingham mistook the Inca citadel for Manco’s last stronghold. The true Vilcabamba was identified in 1964 by explorer Gene Savoy, putting to rest Bingham’s postulation that Vilcabamba and Machu Picchu were the same place.

Savoy cleared as much of the ruins as he could, but it was quickly swallowed back up into the jungle shroud, obscuring for several more decades an estimated 400 structures, most of them partially or completely buried.

That’s how Fonseca found the site when he was sent there after joining the regional Cusco directorate of the National Institute of Culture (now the Ministry of Culture) in 2008.

“At that time I was 29 years old, single and I was the new guy,” he said, “so I had to go where they sent me.”

“When I got to the place I felt a special connection with the area, almost as if it was inviting me to stay,” Fonseca added. “I stayed put there, working in this wilderness, dense with vegetation and with many technical and material limitations, practically incommunicado due to the geography of the zone, together with my team working elbow to elbow.”

Then in July of last year, they hit pay dirt: a funerary complex that they painstakingly uncovered, layer-by-layer for the next three months.

“All of the objects found were extracted with a lot of care, adopting every measure of security possible,” he said. “The problem was getting it all to Cusco. When we had the pieces in our hands, we had to transport them in a caravan on foot, the entire team; 20 of us.”

Setting out on Nov. 20, they hiked for hours to the next closest population center, where they hired a vehicle. But there would be more obstacles in their path.

“We encountered a landslide right smack in the middle of the road and we had to continue on by foot,” he said. “Hours later we got to Quillabamba and we were able to finally get a bus to Cusco.”

But the relief they felt as they drove was tempered by the responsibility they felt toward their fragile cargo. Ensuring the relics did not fragment or deteriorate remained a constant concern.

“Being out in the bush in that zone, and the care with which we had to the transport made it all feel like something of an Odyssey,” said Fonseca, “but it was worth the trouble.”

Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking

Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking  The Cusco School of Painting

The Cusco School of Painting  Pirates in Peru and the Lima DVD dilemma

Pirates in Peru and the Lima DVD dilemma  Inca Trail Weather Forecast System Gets Update

Inca Trail Weather Forecast System Gets Update  A new bridge to Machu Picchu

A new bridge to Machu Picchu  Underwater tomb discovered in Lambayeque along Peru’s northern coast

Underwater tomb discovered in Lambayeque along Peru’s northern coast  Moche – Phase I through IV

Moche – Phase I through IV  Cable Car Connecting Sacred Valley And Huchuy Qosqo Approved By Peru Tourism Ministry

Cable Car Connecting Sacred Valley And Huchuy Qosqo Approved By Peru Tourism Ministry