Ruins vs. the archaeological complexes: How they’re getting it right with the Moche Temples

“It is said that when the anthropologists arrive, the gods depart. In my opinion, something similar happens with reconstructors of archaeological sites. Imagination is crushed; the mystery, the allure and the enchantment depart. (Many archaeologists would add: and with them goes a lot of irreplaceable information; for these are sites that can no longer be studied in their particulars.)”

— Peter Frost, Exploring Cusco

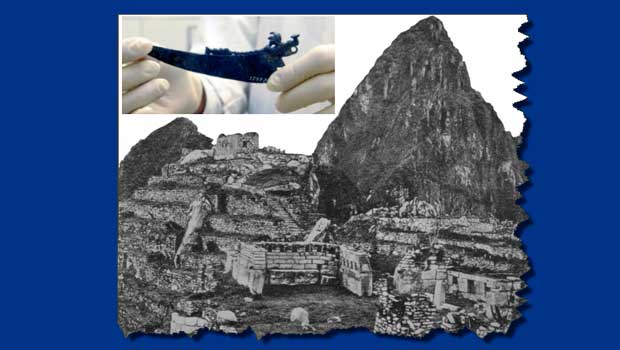

Despite its popular reputation as a pristine, intact archaeological complex, people are surprised to learn that many of the outlying buildings of Machu Picchu were in fact collapsed piles of stone in July 1911, when Hiram Bingham first reached the site.

Masterfully interlocking Inca masonry was covered, penetrated and upended by dense vegetation, thick vines and trees that took root during centuries of abandonment.

Bingham cleared the site during his renowned 1911 and 1912 expeditions. Over ensuing decades, those same structures were repeatedly shored up.

That was the case before and after the earthquake that devastated Cusco in 1950, and particularly during the 1970s, when Peru embarked on a wholesale tidying up of many of the country’s major archaeological complexes throughout the country.

“One of the policies of this archaeological project is that we reconstruct absolutely nothing,” says Dr. Henry Gayoso, the archaeologist in charge of the curatorial content at the site. “Reconstruction: zero. Conservation: everything we can possibly conserve.”

Here, visitors tread over elaborately laid scaffolds, an arms reach from incredibly well-preserved murals and bas-relief carvings depicting mythical creatures, anthropomorphic deities and sacrificial religious rituals framed by intricate geometric borders.

German archaeologist Max Uhle initiated studies of the complex in 1899, but the massive temple went largely ignored for much of the 20th century.

Studies resumed in 1991 and determined that temple was the main center of Moche religious authority from around from about 100 to 600 C.E. (Common Era).

That was also the case for the Aztec Pyramids of Mexico, he added. “Archaeology changes. The methods change. During that time, the correct thing to do was to reconstruct. But not now; not here.”

To be continued….

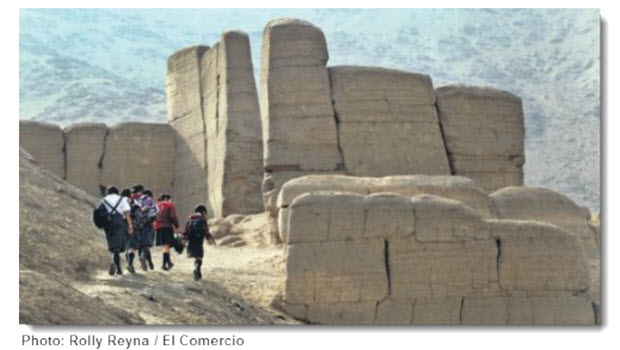

Lost Huacas: the challenge of reclaiming Lima’s pre-Columbian past

Lost Huacas: the challenge of reclaiming Lima’s pre-Columbian past  The Caretakers of Machu Picchu

The Caretakers of Machu Picchu  The Cusco School of Painting

The Cusco School of Painting  Momentum mounting for stronger laws to protect Peru’s endangered Andean Condor

Momentum mounting for stronger laws to protect Peru’s endangered Andean Condor  How to make Lomo Saltado?

How to make Lomo Saltado?  The final program for Machu Picchu 100-year anniversary celebration

The final program for Machu Picchu 100-year anniversary celebration  Yale and Cusco university sign deal for return of Machu Picchu artifacts

Yale and Cusco university sign deal for return of Machu Picchu artifacts  Antonio Banderas’ tribute to the Inca Trail, Machu Picchu & Peruvian friends

Antonio Banderas’ tribute to the Inca Trail, Machu Picchu & Peruvian friends