Klondike-style gold rush in Peru’s southern jungle threatens carbon offset deals

My friend Barbara Fraser, one of the leading environmental reporters in Peru, published a story today in The Daily Climate describing how accelerated gold exploitation is eating away at the jungle department of Madre de Dios like a cancer.

As technical a topic as carbon offsetting might seem to many, Barbara’s story makes plain that we are all witnessing a missed opportunity to help stave off global warming by preserving Peru’s Amazon jungle.

A newly paved road — and soaring gold prices — have triggered a Klondike-style gold rush in Peru’s rain forest, choking waterways with sediment, and threatening the country’s ability to preserve the forest via profitable carbon-offset deals. Photograph © Barbara Fraser.

The two highest income generators for Madre de Dios are gold mining and timber extraction, which is equally devastating, as well as unregulated and illicit. Both of these deforesting enterprises compete with a green alternative, eco-tourism.

Madre de Dios is Peru’s top nature tourism destination, but it, too, is threatened by encroaching gold exploitation.

“As one area plays out, the miners move on,” Barbara wrote. “They recently invaded the buffer zone of the Tambopata Natural Reserve, fending off police who tried to dislodge them.”

A year ago, the Peruvian government established “go” and “no-go” zones for mining in Madre de Dios, but that isn’t solving the problem, Barbara explained to me. A multi-agency approach is needed. The tax authorities, Labor Ministry, Health Ministry, Energy and Mines Ministry, Environment Ministry, police and public prosecutors need to act together.

Other facts that Barbara points out:

Regional government officials in Madre de Dios say mining drives about 80 percent of the regional economy, and with international gold prices at about $1,300 an ounce, there is nothing more profitable than mining. That causes inevitable conflicts, as some indigenous communities and small farmers turn to mining, or rent some of their land to miners, to take advantage of the immediate profit, without thought of the long-term consequences for health and the environment.

Too little attention is being paid to the health hazards of mercury use. Recent studies by the Ministry of Production have confirmed a preliminary study done in November 2009 by Luis Fernández of Stanford University, who found high mercury levels in some of the fish most commonly sold in the Puerto Maldonado market.

Fernández and researchers from the US Environmental Protection Agency have also found high levels of mercury in the air in and around the shops that buy and sell gold and mercury in Puerto Maldonado. Those shops are across the street from the city’s biggest market, and people in the market — including pregnant women and small children — are being exposed to mercury all day every day.

Mercury is very toxic and causes lasting neurological damage. And the urban exposure is unnecessary. Air-quality standards could be set and shops could be required to install filters and other devices to vent safely.

More of the same.

What Barbara covered here on her environmental beat is nothing new. It’s more of the same, only getting much worse.

In the book Beyond the Silencing of Guns, published nearly a decade ago, there is a chapter by Maria Bedoya titled Gold Mining and Indigenous Conflict in Peru that details the history and legal structure of gold exploitation in Madre de Dios.

From the time of the conquest in the mid-16th century to the mid-19th century the Spanish made several unsuccessful attempts to enter the region, including an expedition led by Juan Alvarez de Maldonado in 1567, after which commercial interest in the area waned.

From the mid-19th century to 1895, new scientific expeditions were launched, led by Markham, Raimondi, Gardner-Gibbon and Faustino Maldonado. The explored the geography with an eye toward extracting natural resources. During Maldonado’s expedition, the course of the Madre de Dios River was discovered, opening a new route for the commercialization of rubber.

The rubber boom lasted 1890 into the 1920s.

A period of “stagnation” occurred in the rubber industry, but in the 1930s a gold boom started. That petered out and was replaced by the extraction of chestnuts for export. In 1973, a new gold rush began, but then, as now, without government regulation.

“From the economic point of view, mining brings almost nothing to the Department, in terms of taxes,” Bedoya wrote. “There is no system to control the sale of gold, thus the mining tax cannot be collected.”

In evocative detail, Barbara recounts how the mud-covered workers using mercury to isolate and extract the gold, and then “hand the lump over to the owner of the operation, who will break off a piece to pay them.”

How does Peru’s government tax a transaction like that?

What you can do to help.

Imagine if your vacation could help turn this situation around.

One of the most effective things you can do to protect and preserve Peru’s southern Amazon jungle is to visit one of the eco-lodges in the Tambopata Reserve outside of Puerto Maldonado. It doesn’t even have to be with Fertur Peru, although we’d be honored to have your business.

Your tourism dollars offer the best and most viable alternative for the people of region, empowering them to reject the gold mining.

Excerpt:

“At the end of the day, the men will scoop up the sand trapped on the carpet, add mercury, mix it to form an amalgamated lump of mercury and gold, burn off the mercury and hand the lump over to the owner of the operation, who will break off a piece to pay them. When the pit plays out, they will move on, leaving hectares of stripped earth and sediment-choked waterways behind.”

“Heavily forested Madre de Dios, Peru’s top nature tourism destination, is a prime target for carbon-trading schemes such as REDD, or Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, and REDD+, which includes forests not necessarily threatened. But those schemes, which took a step forward in the United Nations climate talks in Cancún in December, are being overtaken by mining and other development.”

April 1 reopening of Machu Picchu could be a rough ride

April 1 reopening of Machu Picchu could be a rough ride  Peruvian Congress pushes for new road access to Machu Picchu

Peruvian Congress pushes for new road access to Machu Picchu  Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking

Peru, Mexico and Ecuador seek global campaign to confront antiquities trafficking  Nothing Plastic about Machu Picchu, that’s the Goal

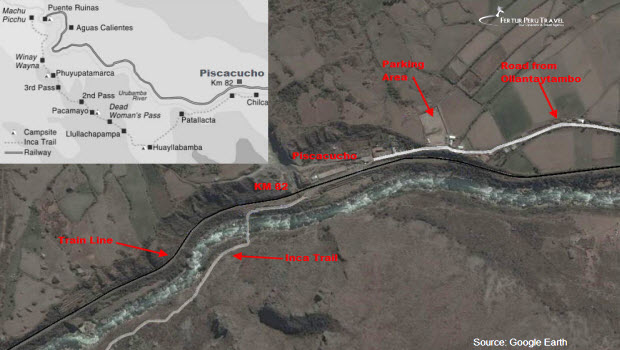

Nothing Plastic about Machu Picchu, that’s the Goal  New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu

New Train Service from Ollantaytambo to Machu Picchu  Hidden Inca treasure in the old headlines

Hidden Inca treasure in the old headlines  Mr. Monopoly Tours Lima in Search of Votes

Mr. Monopoly Tours Lima in Search of Votes

Mercury levels thruout Madre de Dios are off the scale. There is no safe method to visit this region.