Discovery: The Inca Rebellion of 1536

Originally published in South American Explorer Issue #85 Summer 2007.

Why just read about this fascinating archaeological discovery? Experience it up close. Click Inca Rebellion Archaeological Tour to learn more.

Archaeologist Guillermo Cock

In August 1536, some 50,000 warriors marched on Lima under the command of Manco Inca’s most valiant general, Quizo Yupanqui, with orders to kill every Spaniard in the newly founded capital.

For more than 470 years, all there was to know about the events of the six-day Siege of Lima had to be gleaned from the often-contradictory historical record left by early colonial chroniclers.

But in 2007, an international team of scientists led by Peruvian archaeologist Guillermo Cock uncovered the remains of 35 apparent Inca casualties from the uprising – among them men, women and adolescents, and a forensically proven case of the first gunshot victim ever found from the Conquest era.

Cock, who has spent the last quarter century trying to unravel the mystery of the Inca Empire and its demise, was asked by the city of Lima in 2004 to dig a test trench in the Andean foothills on the eastern outskirts of the city ahead of a planned road project.

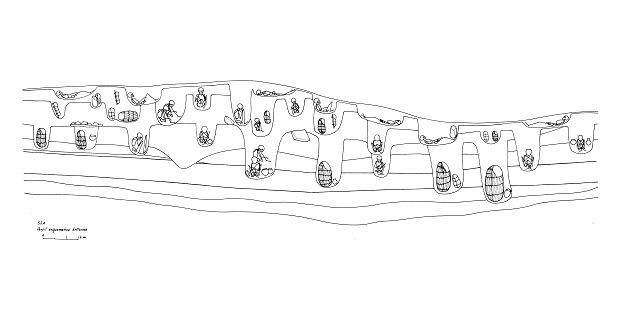

In the 20- by 80-foot excavation, Cock and longtime archaeologist colleague Elena Goycochea quickly discovered the site had been a cemetery dating back some 500 years to the Inca civilization.

More than 425 skeletons were exhumed, and 140 were carefully examined. Cock found that 72 of the bodies on the hillside were buried without the usual Inca reverence for death – ritually wrapped in yards of raw cotton and entombed with funerary offerings in a flexed position, with the knees pulled up to the chin, and facing the northeast.

Battle casualty from 1536 Inca Uprising

About three dozen of the bodies were found in unusually shallow graves, and many “showed signs of terrible violence,” Cock said. “They had been hacked, torn, impaled — injuries that looked as if they had been caused by iron weapons — and several had injuries on their heads and faces that looked as if they were caused by gunshots.”

“Everything would suggest that they had been buried in a hurry,” he added. “Very soon we realized that the only event that we could associate the remains with was the Siege of Lima in 1536.”

The cemetery lies less than a half-mile from thousands of Inca mummy bundles discovered by Cock at Puruchuco-Huaquerones beginning in 1999, which offered a breathtaking window to Peru’s Late Horizon period, providing the clearest and most complete view archaeologists have ever had of everyday life during the Inca’s reign from 1438 to 1532.

This new cemetery, Cock said, pinpoints the brutally violent historic transition from Inca imperial rule to the Spanish Colonial era.

“Never before in the history of American archaeology have the remains of natives killed during the Conquest process been found and we have a few of them,” said Cock. “It confirms the events and shows us in a very graphic way how violent the process was.”

Bio-archaeologist Melissa Murphy

In Cock’s laboratory in Lima, team member and bio-archaeologist Melissa Murphy of Bryn Mawr College examined skeletal remains carefully laid out on long examining tables.

One was a woman whose face had been bashed in. The other was a young man with gunshot wound through the head.

“We have a mix of traumatic perimortum, or injuries that occurred at or around the time of death, many of them to the crania of adults, children,

both man, woman and child,” Murphy said. “Some of the injuries are blunt force trauma, that is they have an injury caused by some sort of blunt object, an ax, a mace. Some of the injuries are clearly sustained from Spanish or European weapons.”

It is the discovery of the gunshot victim, however, that has caused the most excitement.

National Geographic, which has helped fund Cock’s research, announced the find on June 20, 2007, after scientists from New Haven’s Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science in Connecticut scanned the skull with an electronic microscope and found the wound was impregnated with fragments of iron – a metal unknown in pre-Hispanic Peru, but one that was sometimes used for Spanish musket balls.

Cock said when he first spotted the partially excavated skeleton in 2004, facedown, with a hole through the head, he attributed it to vandals firing handguns into the ground, but quickly realized that the velocity and force of a modern bullet would have shattered the skull.

“The bullet projectiles used in the past were not only different in shape but also traveled at a much lower speed,” Cock said. “The preferred bullets were made with lead, because this is a soft metal that is really heavy, that can be shaped quickly. But they did not have that kind of metal available … They were shooting whatever gunpowder was able to propel.”

Murphy said she was “blown away” when she first saw the field photographs of the gunshot wound. “I did a double take for a minute because I thought, ‘We’re not supposed to see gunshot trauma in this sample, and there’s not supposed to be gunshot wounds.’”

The team consulted with an old friend and colleague, physical anthropologist John Verano of Tulane University – who has used modern forensic techniques to document ritual torture and killing during the pre-Inca Moche culture – and he agreed that a gunshot caused the injury.

Later, sifting through the facial fragments trying to reconstruct the skull, Murphy found the “plug” of bone blown out from the exit wound, which also bore an internal bevel – a telltale sign in modern forensics to identify postmortem gunshot victims.

“You can see on the plug that there’s one side that’s smaller that actually fits perfectly into where the projectile entered the cranium,” she said.

Manco Inca

The Great Inca Rebellion of 1536 began when Manco Inca, the Conquistador’s puppet ruler, grew tired of abuses by his Spanish masters.

After a brief but harsh imprisonment in late 1535 for trying to escape, Manco Inca persuaded Francisco Pizarro’s younger half-brother Hernando – recently appointed lieutenant governor of Cuzco – to allow him to leave the Inca capital. He beguiled his captor with a promise to bring back a life-sized golden statue of his father Huayna Capac if he was allowed to leave.[1]

Instead, he met with Inca chiefs to finalize plans for a huge mobilization of Inca warriors to kill the Spanish and forever drive the European invaders from his devastated land.[2]

Years before Francisco Pizarro stepped foot on Peruvian soil, a wave of pestilence rivaling the Black Death in 14th Century Europe had been unleashed by early explorers in Mexico and the Caribbean years earlier. Highly contagious diseases like smallpox, measles and typhus, to which native Americans had never been exposed, swept through the hemisphere, wiping out perhaps 50 to 90 percent of the indigenous population as it traveled southward.[3]

When Pizarro’s party landed on Peru’s northern coast in 1532, they were told of a disease that ravaged the Inca Empire years earlier. The epidemic, probably small pox, killed thousands, including the ruler, Huayna Capac, whose army and court were struck down by delirious fever sometime between 1525 and 1527.[4]

Huayna Capac’s death sparked a civil war of dynastic succession between his two eldest sons, Huascar and Atahualpa, and facilitated the Spaniard’s conquest of a split Inca Empire, which stretched for nearly 3,000 miles along the Andes from the south of modern-day Colombia to central Chile.

Cock said the Inca battle cemetery sheds light on how Francisco Pizarro deftly forged alliances with native tribes that viewed the Inca as a common enemy. Most of the empire’s populace had fallen under Inca control during a lightning fast rise that spanned only three or four generations.

The skeletons recovered by Cock’s team bear battle scars inflicted by both sides of the Spanish-native military alliances against the Inca.

“There some individuals who have injuries that were sustained from Spanish or European weapons,” Murphy said. “And then there are some individuals that have injuries that were sustained from indigenous weapons, star-shaped maces or perhaps some type of wooden axes or bole stones or sling stones.

“There’s this myth perpetuated that there was, you know, 147 Spaniards and they conquered armies of thousands of indigenous” warriors, Murphy said. “But we know there were people who were very resentful of being under Inca control, so when the Spanish arrived they received the Spaniards as being liberators.”

In the mid-15th century, the Rimac and Lurin valleys formed a polity known as the Señorio del Ichma, which had made an alliance with the Inca Empire when it pressed military expansion throughout the region before falling under Spanish control.

One of its four districts was known as Lati, modern-day Ate-Vitarte, the impoverished district in Lima’s outlying Andean foothills where Cock discovered the Inca cemetery.

Lati also was identified by Inca chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala nearly 80 years after the siege of Lima as the site of Quizo Yupanqui’s death in battle.

“Guaman Poma tells that Quizo Yupanqui was killed next to the Lati canal and the cemetery that we excavated is next to one of the Lati canals,” Cock said.

“I doubt that we have the body of Quizo Yupanqui,” Cock added. “I am pretty sure that he was taken back to his native land to the place where he was born and buried there.”

Before Quizo Yupanqui’s attack on Lima, he had embarked on a deadly campaign against the Spanish across the central Andes while Manco Inca laid siege to Cuzco.

Francisco Pizarro, fearing for his brothers’ safety, dispatched five rescue parties in succession from Lima to relieve the Spanish outposts under attack.[5]

None of the parties reached their destinations. Four were annihilated by Quizo Yupanqui’s forces – including four of Pizarro’s captains, nearly 200 men and many horses.[6]

Lima Mayor Francisco de Gadoy led the fifth group, but upon learning the about other defeats from a survivor, he chose to retreat without ever facing the enemy – sealing a mark of dishonor that followed him to the grave. Chronicler Agustín de Zárate would write nearly 20 years later that Gadoy returned to Lima “with his tail between his legs.”[7]

Peruvian historian Edmundo Guillén Guillén writes that upon learning about the sensational triumphs, Manco Inca ordered Quizo Yupanqui to immediate attack Lima and destroy Pizarro’s weakened garrison before he could send for reinforcements from Panama, Santa Domingo and Guatemala.

“It is important to clarify the point that, as in Cusco, the 500 Spaniards were not alone in defending the city,” Guillén wrote. “Rather they counted on the support of curacas (local indigenous leaders) and yanakunas (native house servants) from the Lima valley and other neighboring districts, plus 4,000 (native) men from Waylas.”[8]

Cock said Pizarro also had on his side Peruvian Huanca warriors, African slaves and Nabororías Indians from Nicaragua, who were trained in the art of the “short sword” and how to slice open the stomachs of the opposing Inca forces.

Quizo Yupanqui did not immediately attack as ordered by his Inca ruler. Instead, he spent July 1536 trying to persuade anti-Inca tribes like the Jaujas, Huancas and Yauyos to turn against the Spanish invaders to ensure against attacks on his rear guard.[9] Much of his success against the Spanish forces in the highlands was owed to the dramatic topography that allowed Inca warriors to shower avalanches of rocks and boulders on their enemy and their horses from higher ground. The Inca general understandably wanted to assemble an overwhelming force before engaging deadly Spanish horsemen on the unfamiliar level battlefield of Lima’s coastal plain.[10]

The Inca forces’ protective gear – wooden helmets (humachuko), small wooden or leather shields (wallkanka) and padded animal skins for armor – had proven no match for Spanish infantry armed with steel swords, pikes, halberds and harquebus firearms. In contrast, a mounted conquistador in armor was virtually impervious to the stone- or copper-tipped spears (chuki), slings (waraka), bows (peqta) and axes and clubs (kunka kuchuna) of the Inca.[11]

As the siege of Cuzco wore on in the southern highlands and Quizo Yupanqui prepared to march on Lima, a psychological war of terror was waged on both sides.

“I can bear witness that this is the most dreadful and cruel war in the world,” Alonso Enríquez de Guzmán wrote in 1543, recalling the Inca rebellion. “For between Christians and Moors there is some well-feeling, and it is in the interests of both sides to spare those they take alive because of their ransoms. But in this Indian war there is no such feeling on either side. They give each other the cruelest deaths they can imagine.”[12]

Inca forces cut off the limbs of Spanish soldiers who fell into their hands, while the Spaniards targeted the Inca warriors’ wives who played a crucial role carrying supplies, cooking and caring for the wounded.[13]

“Seeing the perseverance behind the siege of the city (Cuzco), Hernando Pizarro ordered the Spanish not to leave any woman alive,” one anonymous Spanish chronicler later wrote. “The fear generated in those who remained free would keep them from serving their husbands. This was done from thence on, and so good was the stratagem that it sowed much dread, as much in the Indians of losing their women as the women who feared to die.”[14]

Evidence from the Inca cemetery suggests that a similar policy against the families of Inca soldiers, who were basically formed a peasant militia, was similarly employed in Lima.

Murphy said she maintained a “certain detachment” when she examined signs of brutal death evident in the remains of the men, women and adolescents uncovered so far.

“I think the hardest thing to face is actually looking at the children who have injuries because those are really the innocents. Those are the hardest victims to examine,” she said. “I felt a little dread and kind of some sorrow as well because you’re providing evidence for something that everyone knows what the outcome was, and it’s a pretty horrific tale.”

Quizo and his army descended to Lima’s outlying Andean foothills in mid-August 1536, three months after the uprising began. Pizarro sent conquistador Pedro de Lerma with a squadron of cavalry to try to halt the Inca’s advance.

A sharp engagement ensued on the open plain two leagues, or about seven miles, from the city. Many Indians lost their lives and one Spanish horseman was felled as the Inca forces moved to higher ground.[15]

When first Pizarro “saw the multitude” of approaching Inca warriors “he believed without any doubt that here our side would perish.”[16]

Quizo’s advancing army crossed the plain, engaging in skirmishes with the Spaniards, but when his warriors reached the outlying houses of the city, Spanish horsemen emerged with lances, impaling many Indians in the ambush, until the Inca warriors again retreated to nearby hills.[17]

That night, while the Spanish cavalry patrolled Lima’s streets, Quizo moved his army under the cover of darkness to the Cerro de San Cristóbal, a steep Andean foothill just across the Rimac River from the center of Lima. Other native tribes occupied hills to the northeast of Lima and between the city and its port in Callao, thus surrounding the Spanish and virtually severing their communications with the sea.[18]

There, they remained impervious to attack by cavalry and for five days they waited, while the Spanish planned a nighttime attack to dislodge them. The Spaniards agreed to build a huge shield of wooden planks to protect themselves from hurled stones, but in the end, it was too heavy to lift.[19]

On the sixth day, Quizo, impatient with the stalemate, decided it was time for action. Gathering his top commanders, he said: “I want to enter the city today and kill all the Spaniards that are there, and take their women to marry and we will create a strong new generation of warriors.”[20]

He made his commanders pledge, “If I die, we all die and if I flee we all flee.”

Waving banners and beating war drums, the Inca warriors charged down the hill and forded the two branches of the Rimac River, all the while letting out a battle cry: “Into the sea bearded ones! Into the sea bearded ones!” [21]

Pizarro at once ordered his remaining cavalry to form into two squadrons, placing one under the command of a captain to hide on one street, and he led the other contingent to another street, waiting in silence.[22]

Quizo “entered the streets of Lima, and some of his people advanced along the tops of walls. The cavalry charged out in a sharp attack. Since the ground was flat, they were routed at once and the general was left there dead and so were forty captains and other chiefs.” [23]

This is just one other version of Quizo’s death from the often-cited Relacion del Sitio del Cuzco, an eyewitness account written in 1535 by an unknown author. Pedro Martin de Sicilia claimed he wielded the lance that pierced Quizo Yupanqui’s chest.[24]

Guaman Poma placed Quizo’s death seven miles away in Ate-Vitarte, where the Inca cemetery was discovered.

Chronicler Martín de Murúa wrote that Quizo Yupanqui was struck in the knee by a harquebus bullet and died later of his wound in “Chinchayqota” in the Andean highlands.[25]

Quizo’s captains Illa Thupa and Paukar Waman, seeing their forces decimated, retreated along the northern Canta and southerly route to Huarochirí.[26]

The southerly escape route passed right by the cemetery unearthed by Cock and his team.

[1] Hemming, Conquest of the Incas, 188

[2] Ibid, 188

[3] Roberts, Disease and Death in the New World, Science, Dec. 8, 1989

[4] Ibid

[5] Jose Antonio Del Busto, Francisco Pizarro: El Marquez Gobernador, p. 210

[6] Relacion del Sitio del Cuzco, p. 76

[7] Ibid, p. 211

[8] Guillén, Los Incas y el Inicio de la Guerra de Reconquista, p. 600

[9] Hemming, Conquest of the Incas, p. 210

[10] Ibid, p. 210

[11] Guillén, Los Incas y el Inicio de la Guerra de Reconquista, p. 593

[12] Hemming Conquest of the Incas, p. 204

[13] Ibid, p. 204

[14] Relacion del Sitio del Cuzco, p. 43

[15] Ibid, p. 77

[16] Ibid, p. 77-78

[17] Ibid. p. 78.

[18] Hemming Conquest of the Incas, p. 210-211

[19] Relacion del Sitio del Cuzco, p. 79

[20] Ibid, p. 80

[21] Jose Antonio Del Busto, Francisco Pizarro: El Marquez Gobernador, p. 213

[22] Ibid, p. 213

[23] Relacion del Sitio del Cuzco, p. 80-81

[24] Jose Antonio Del Busto, Francisco Pizarro: El Marquez Gobernador, p. 214

[25] Guillén, Los Incas y el Inicio de la Guerra de Reconquista, p. 601

[26] Ibid, p. 601

Extra! Extra! Crowds through the clouds to Choquequirao

Extra! Extra! Crowds through the clouds to Choquequirao  Peru’s last Inca Rope Bridge Gets CNN’s Attention

Peru’s last Inca Rope Bridge Gets CNN’s Attention  Organic EcoSMART insect repellent stands up to toughest Mochica mosquitos

Organic EcoSMART insect repellent stands up to toughest Mochica mosquitos  The History of Surfing in Peru

The History of Surfing in Peru  Blitzing the Incas

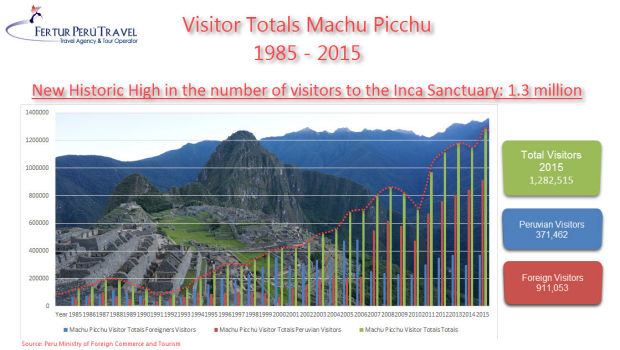

Blitzing the Incas  Is Machu Picchu losing its allure with record numbers flocking to the site?

Is Machu Picchu losing its allure with record numbers flocking to the site?  How to make Lomo Saltado?

How to make Lomo Saltado?  Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum

Inca Rebellion – Puruchuco Exhibit Opens at Peru’s National Museum